Stars are giant balls of hot gas, mostly hydrogen. The cores are nuclear furnaces where hydrogen atoms are fused into helium, releasing energy, that takes millions of years to radiate to the surface. When low-mass stars like our Sun run out of hydrogen to fuel into helium, they balloon up into a red giant, violently shed the outer layers in a supernova explosion, and leave behind a dense core, called a white dwarf. A white dwarf is a stellar remnant that packs in the mass of the Sun into an object about the size of the Earth. Over billions of years, the core of the dead star continues to burn, slowly cooling down. RXJ0528+2838 is one such white dwarf, at a distance of 730 light years from the Earth.

Many white dwarfs are in binary systems, paired with a companion star. In such systems, an alive star and the dead star orbit around a common centre. The white dwarf begins to parasitically feed on the atmosphere of the companion. The accreting gas forms a spinning disk around the white dwarf, similar to the Rings of Saturn, but made up of plasma. The magnetic fields of the accretion disk causes the infalling gas to become viscous, behaving like a liquid. The heat causes the gas to glow, with some of the infalling material ejected outwards as an outflow of high speed gas and dust.

The Nebulosity

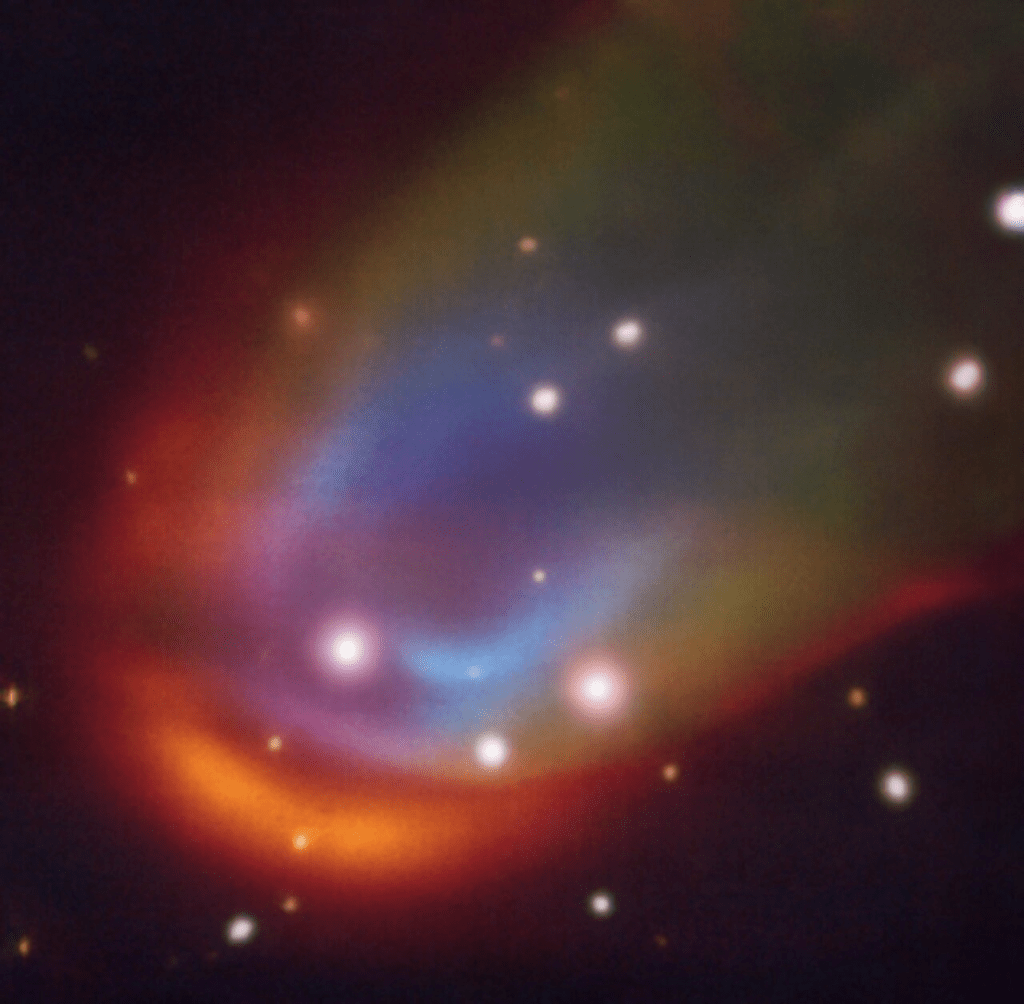

These outflows can then interact with the interstellar medium, the wispy gas filling the space between stars. The binary system, like most stars, orbit the centre of the galaxy, at speeds of around 200 kilometres per second. As the outflows interact with the interstellar medium, a shock wave is created, where the gas compresses and heats up, again forming a glowing structure. When shaped like the wake of a boat, this is called a bow shock. Bow-shocks are common around fast moving-stars with strong outflows, that appear in telescopes as arcs of ionised gas.

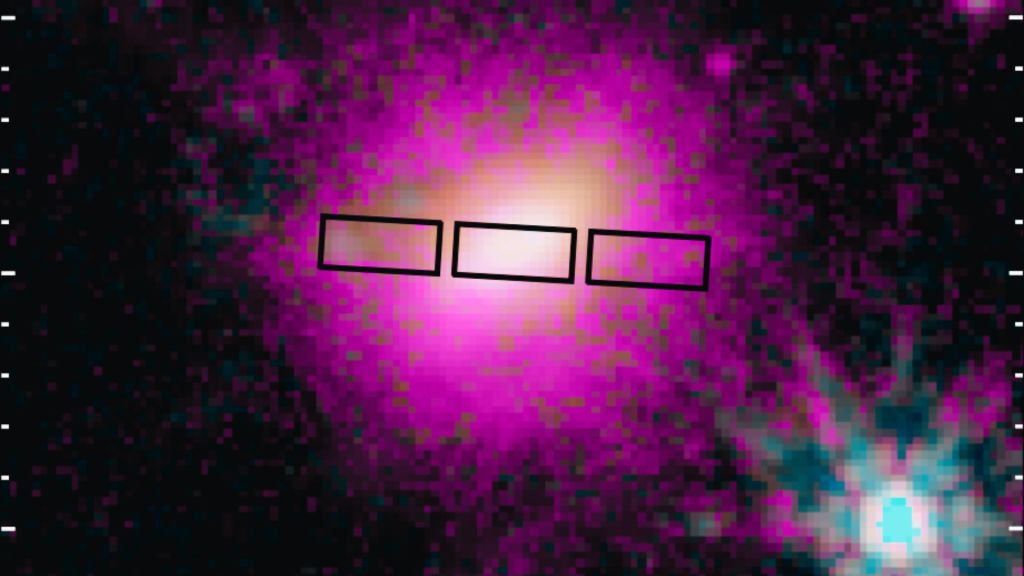

The discovery of the bow shock around RXJ0528+2838 was unexpected. A student first spotted the nebulosity, or a cloudy glow in images captured by the Isaac Newton Telescope in Spain. The shape indicated an unusual process, atypical of a nova remnant from a past explosion. Astronomers conducted follow-up observations with the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, operated by the European Southern Observatory. MUSE splits light into spectra, with careful analysis of the light revealing composition, motion and temperature.

A diskless white dwarf

The observations confirmed that the bow shocks originated from a binary system. It spans about 3,800 astronomical units (AU), where a single AU is the distance between the Earth and the Sun. The shape of the structure and its emissions indicate that it is indeed formed by an outflow colliding with the interstellar gas at the velocity of the system. Still, the discovery is puzzling as such outflows require an accretion disk, whose signature is brightness in infrared frequencies. RXJ0528+2838 shows no infrared excess or spectral lines indicating a disk. The observations challenge conventional theories on the evolution of binary systems, as how can a white dwarf expel enough material to sustain a bow shock without a disk?

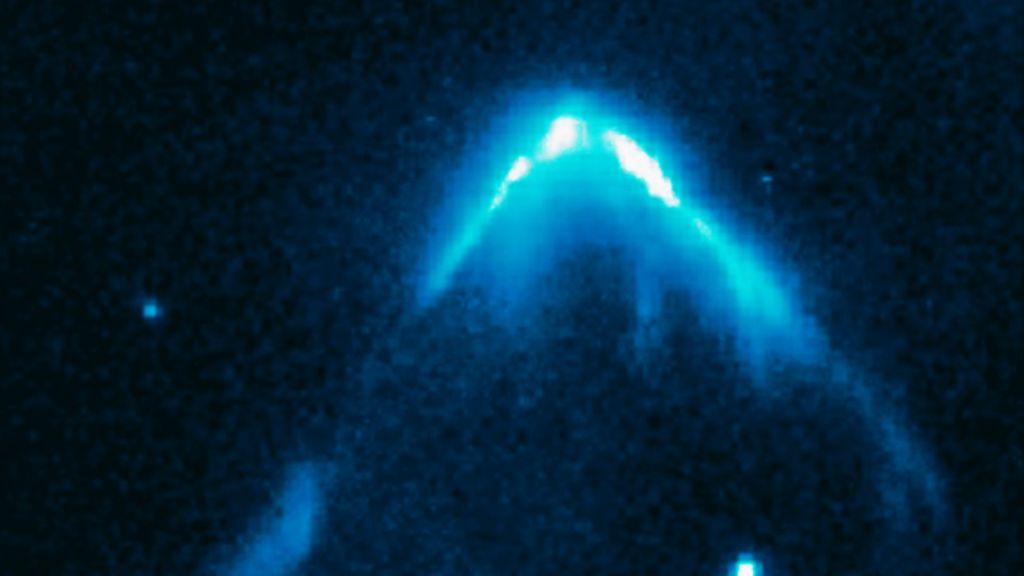

The white dwarf is highly magnetised, and has a magnetic field measured at millions of gauss, far stronger than that of the Earth, which is about 0.5 gauss. Cataclysmic Variable binary systems with highly magnetised white dwarfs are known as polars. There are no accretion disks around the white dwarfs in polar systems. The magnetic field channels incoming gas directly to the poles, bypassing disk formation. This might drive outflows without the disk. Models support the strong field confirmed by MUSE funnels plasma, heating the gas, and ejecting some as jets. The size of the bow shock implies that the outflow lasted for at least a thousand years. The observed field strength can only power such outflows for a few hundred years. Even for a polar system, RXJ0528+2838 possesses an additional, unknown energy source.

Mystery Engine

Astronomers have some ideas on what this mystery engine could be. It might be, residual heat from past accretion, unknown magnetic processes, or underestimated field variations. To find the solution, astronomers need to study more such polar systems. Only a few diskless systems are known, and finding others can help scientists better understanding them. The upcoming Extremely Large Telescope, with its 39 metre mirror will be able to image fainter structures and map compositions in detail. Scientists from 12 institutions across seven countries were involved in the study published in Nature Astronomy.

Image Credit: ESO/K. Iłkiewicz and S. Scaringi et al.

Leave a reply to Interstellar Interlopers – StarBullet.in Cancel reply