Red dwarf stars are the most common stars across the universe, far more common than yellow dwarf stars that burn out in ten billion years, or the blue and white giants that live for only a few million years. These cool, dim stars can burn steadily for 100 billion years, although they are active and tempestuous in their youth. The convention for referring to star systems is to use capital letters for the stars and letters for the planets. Red dwarf C c is the second planet orbiting the tertiary red dwarf in a triple planet system. Red dwarf A and B are in a much tighter orbit around each other. Such configurations are stable and common, and in such a star system, we will be examining the oldest trick in the book of life, a primordial survival strategy, at work on a world in the red edge, just within the habitable zone of the host star, with fluctuating conditions.

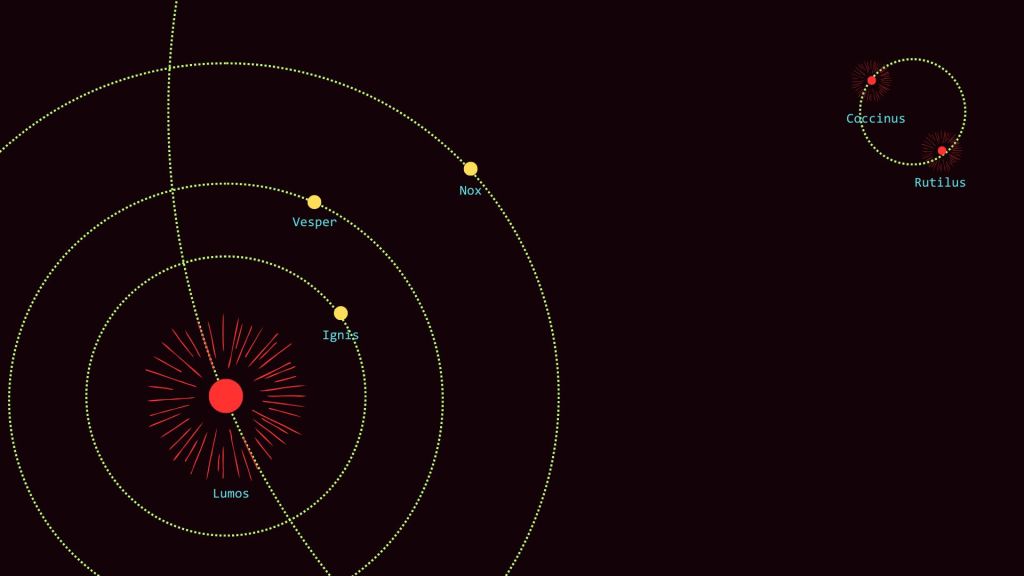

While the simple convention packs in a lot of information about the star system with the judicious use of capitalisation, it is difficult to read, and distracting for a thought experiment, so we are going to bin it, and just name the bodies in this imaginary system. Let us call this rocky exoplanet Vesper, and its ultracool host star Lumos. Vesper orbits Lumos every 20 days at a distance of 0.1 AU, or 15 million kilometres, to stay within the edge of the habitable zone. Lumos also hosts a scorched inferior planet, Ignis that orbits the red dwarf in five days, and a superior planet, Nox that has years 60 days long, and is a frozen gas dwarf. Lumos orbits the binary pair Rutilus and Coccinus at a distance of 450 AU, over a period of 10,000 years. The separation between the twin stars in the binary pair is 10 AU, and they take 40 years to orbit each other.

Vesper is tidally locked to Lumos, with one side constantly facing the star. This dayside has a noon hotspot, with Lumos perpetually occupying the apex point in the sky from where the unrelenting star shines straight down on the planet. The landscape here is desiccated, the water banished. Around other red dwarfs across the universe, this noon hotspot is the only region of habitability on mostly frozen, tidally locked worlds, but not on Vesper. Here, life ekes out a living on the terminator line, the belt of perpetual twilight between the day and night sides. On the far side, the twins Rutilus and Coccinus are making their millennia-long trek across the night sky, casting faint, ghostly shadows. Nox crawls westward, while Ignis moves rapidly around Lumos, with retrograde spurts.

Lumos erupts in solar flares about once every eight days. These violent outbursts suddenly release 100 to 1000 times the regular flux of the star in UV and X-rays. The energetic flares ionise the atmosphere of Vesper, ignite spectacular green-purple auroras, and sear the dayside. The minor flares propel supersonic winds that circle the planet in jetstreams, creating transient icy conditions on the terminator zone and dropping temperatures to 10°C. The weather varies to an incredible extent for a tidally locked world without seasons.

When Lumos is magnetically quiet, temperatures stabilize to between five and 25°C, with water flowing out of the glaciers on the nightside. The star follows a five Earth year (or 91 Vesper year) long magnetic cycle, increasing in luminosity by 10 per cent, with flare intensity increasing by 10 times during the ‘Grand Maxima’. Over a period of two (36) years of the grand maxima, the relentless flares evaporate lakes along the terminator line. During this phase of Lumos, Vesper becomes uninhabitable, an environment too hostile for life.

Prebiotic chemistry had started in the system long before the formation of Vesper, when Lumos was still a protostar, within a warm envelope of gas, in a chemical dance of ice and gas. These complex organic molecules were delivered to the surface through a series of cometary impacts, along with water. The primordial, unicellular organisms clumped together, finding protection in numbers, even though the flaring decimated their populations. Still, over the billions of years, with microbes, seeds and spores using the oldest trick in the book of life.

Dormancy

Dormancy allows organisms, microbial, plant-like, symbiotic colonies, and small multicellular forms, to suspend activity during these the superflare phase. By reducing energy and water demands, they avoid cellular damage from heat, cold, or radiation, reactivating when the habitable phase returns, advanced by thunderstorms that return liquid water to the surface. During the two-year inhospitable phase, superflares bombard Vesper with ultraviolet and X-ray radiation, sterilizing exposed surfaces. On the dayside, temperatures soar past 100°C, evaporating water and baking organic molecules. In the terminator zone, radiation levels spike, and atmospheric shifts cause temporary freezing and aridification. Dormant organisms, encased in protective structures such as spores and sclerotia, resist these extremes. Thick cell walls, desiccation-resistant proteins, and UV-absorbing pigments, evolved under the red dwarf’s constant radiation—enhance survival, allowing life to “hibernate” until the flares subside.

Water availability on Vesper’s terminator zone is precarious. Models of tidally locked M-dwarf planets suggest that while a temperate terminator might exist, it could be arid, with water locked as ice on the nightside or evaporated on the dayside. During the habitable phase, seasonal winds or occasional rainfall might sustain shallow pools or subsurface aquifers. However, superflares could disrupt this balance, driving drought by flash evaporation. Dormancy enables organisms to endure these dry spells by entering a cryptobiotic state, drastically reducing water needs. When water returns via post-flare atmospheric condensation, the dormant life revives, capitalising on the brief window of abundance.

The five-year cycle of habitability and inhospitability imposes a brutal selective pressure, but dormancy offers a solution through a “seed bank” effect. Inactive individuals accumulate in the soil, crevices, or sheltered microhabitats of the terminator zone, preserving genetic diversity and ecological potential. This reservoir ensures that, even if active populations are decimated by superflares, life can rebound rapidly during the habitable phase. Over millennia, this strategy stabilizes ecosystems, with species evolving synchronized life cycles tied to Vesper’s rhythm. On Vesper, there are no mass extinctions.

On Vesper, dormancy shapes both physiology and behavior. Organisms grow rapidly and reproduce during the three-year habitable window, producing dormant propagules just before superflares begin. Microbial mats form tough, radiation-resistant crusts, while larger lifeforms burrow into the regolith, encasing themselves in protective cocoons. Predation and competition peaks early in the habitable phase, tapering off as organisms prepare for dormancy. Evolutionary trade-offs favour resilience over complexity, yielding a biosphere dominated by simple, hardy lifeforms.

The vegetation on Vesper is purple, black and pink, with pigments evolved to use the dim red and infrared light of Lumos. Some plants have reflective yellow spots for protection.

The distant twins, Rutilus and Coccinus gravitationally nudges Vesper over millions of years, expanding and contracting the habitable region around the terminator line by 20 kilometres. The terminator zone’s narrowness limits habitable real estate; overcrowding or resource depletion during the active phase can strain populations before dormancy begins. On Vesper, dormancy might not just be a survival tactic—it could be the cornerstone of a resilient, alien ecology.

Lumos is the most common type of star in the universe, and Vesper is the most common type of planet. These are the hostile conditions that most life in the universe lives in. Below is a real image of a superflare from a binary system of dim red stars called DG Canum Venaticorum, captured by NASA’s Swift satellite on 23 April, 2014. The eruption was 10,000 times more powerful than the strongest solar flare ever recorded.

Sources:

Terminator Habitability: The Case for Limited Water Availability on M-dwarf Planets

Dormancy in the origin, evolution and persistence of life on Earth

Image Credits:

Illustration of a habitable terminator zone: Ana Lobo / UCI

Illustration of a superflare from a red dwarf: NASA SVS

DG CVn X-ray image courtesy of NASA/Swift

Leave a comment