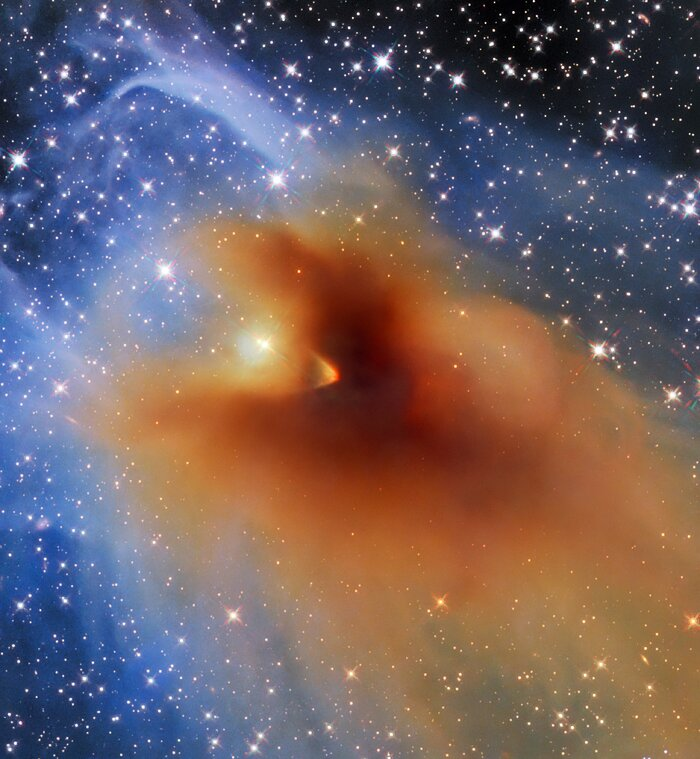

Stellar nurseries are vast clouds of gas, within which entire clusters of stars are born at once. These are clouds reach the lowest temperatures physically possible, and as the temperature drops, the molecules of gas get closer together. Under the influence of gravity, the gas clumps into knots, with matter starting to fall inwards. The mass collapses into a dense core, a compact object where temperatures and density begin to rise.

As the material continues to fall into the protostar, temperatures and densities rise to levels that can sustain nuclear fusion, marking the birth of a star. A newborn star is surrounded by a disc of infalling material, the assembly site for planets. The gas giants made from primordial gas have a hydrogen and helium rich atmosphere, which is the base line composition for all planets, everywhere in the universe.

The first generation of stars were made up of hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements of the periodic table, and the matter that formed after the Big Bang. All the heavier elements were progressively cooked in the hearts of stars. The first stellar nurseries spawned massive clusters of giant, short lived stars that exploded in violent supernovae. These stars, all born around the same time, died together as well, in overlapping explosions similar to a string of fireworks.

Subsequent generations of stars and planets enrich the environment, progressively introducing the heavier elements, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, silicon, phosphorus, sulphur, chlorine, potassium, calcium and iron. This rich chemical inventory results in a range of ices and vapours that can combine in magical ways. The subsequent generation of stars are made from mostly hydrogen and helium gas as well, along with dust and ice in small quantities.

Gas Giants

There is not enough leftover material in the inner regions of an accretion disc around a baby star to form giant planets, that can only accumulate in the fringes of the system. After being assembled though, gas giants can migrate inwards towards their host stars, into increasingly tighter orbits. As the proximity with the star increases, there is an injection of heat into the atmosphere, changing the atmospheric chemistry.

WASP-76 b has dayside temperatures that can reach 2400°C, hot enough to vapourise metals. When winds carry the clouds to the night side, it rains iron.

WASP-127 b has winds blowing at 9 kmps, six times the speed at which the gas giant is rotating. There is water vapour and carbon monoxide in the atmosphere.

KELT-20 b is hot enough to break thermodynamics, with the UV radiation creating a layer of gaseous metals, that inverts the temperature gradient of the atmosphere.

WASP-121 b has been distorted into an oblate spheroid. The temperatures are high enough to sustain heavy metals in the upper atmosphere.

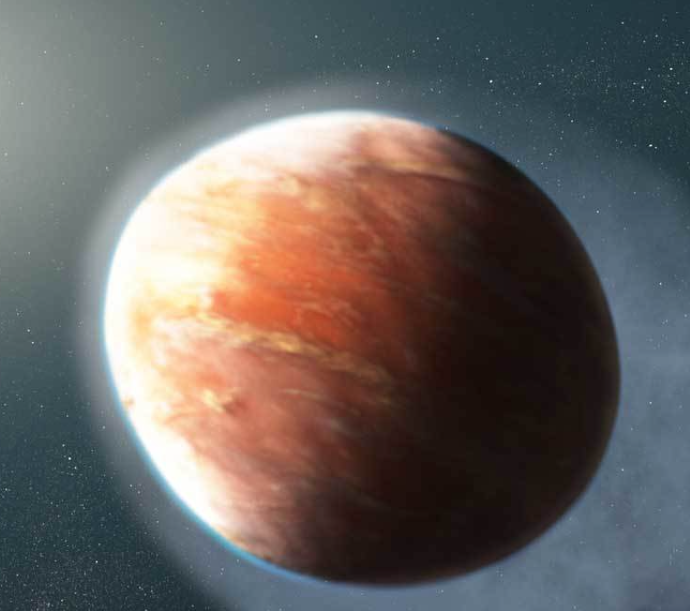

The temperatures rise, methane in gas giants gives way to carbon monoxide. Stellar irradiation can dissociate molecules in the planetary atmospheres, but water molecules can survive even in very hot Jupiters, alongside alkali metals. Depending on the temperature of the world, a different mixture of chemicals occupy the various layers of the atmosphere. With higher temperatures, the altitudes of the heavier elements increase.

These extreme gas giants may have silicon and iron vapour in the atmospheres, with the metallic skies turning them so reflective, that the whole world may act as a mirror. The heat can cause the atmosphere to swell up like a Hot Air Balloon, and the gravitational influence of a host star can begin to tear a world apart. These worlds can expand to 90 per cent the size of Jupiter, while containing only 10 per cent of the mass.

The proximity to the host stars results in the Hot Jupiters getting tidally locked, with permanent day and night sides, separated by the terminator zone of neverending twilight. The day side temperatures can be considerably higher than the night side temperatures, resulting in high velocity winds circling the planet. Cloud cover plays a role in exposing the deeper layers to irradiation and photochemistry.

On such worlds, rubies and sapphires can rain down, within hurricanes of glass. High pressure zones can crystallize carbon, resulting in diamond dust storms. The extreme pressure gradients and supersonic winds can create shock fronts. The host star can also continuously boil away the atmosphere, stripping the giant to its core. Magnetic interactions would result in incredibly spectacular auroras, that shimmer in curtains of ultraviolet and X-ray light.

Ice Worlds

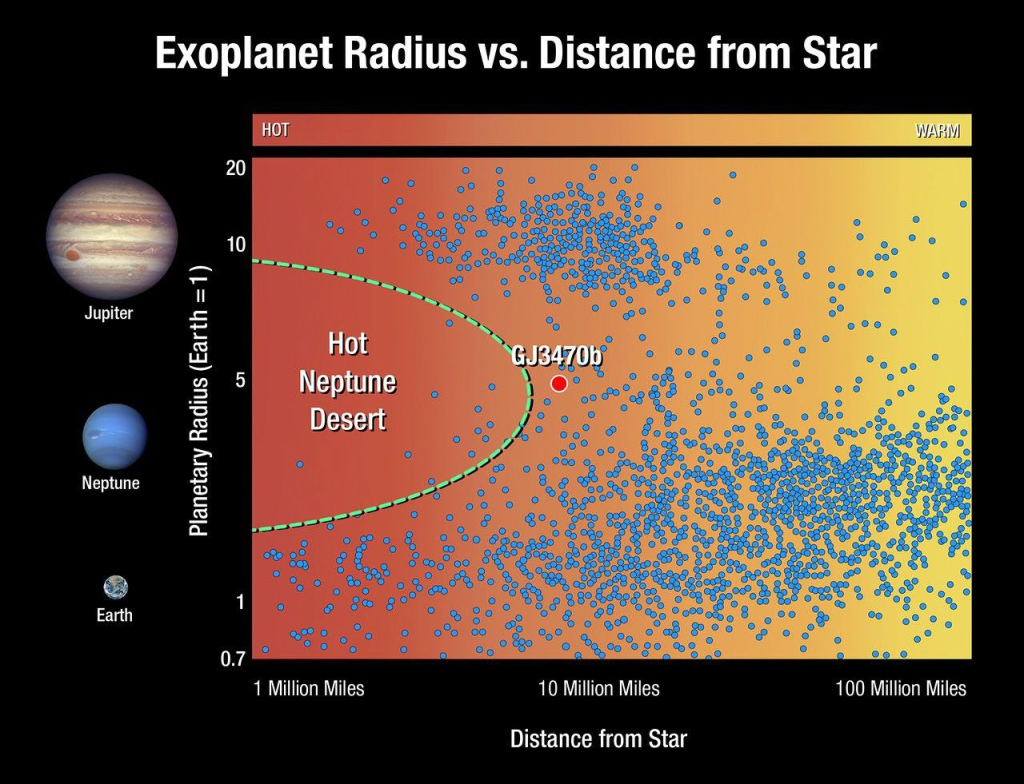

Ice Giants, the more diminutive cousins of the gas giants also go through a gauntlet of similar conditions. These worlds are known as Sub Neptunes or Super Earths, depending on how massive they are. The range of worlds that straddle the mass gap between rocky worlds and ice giants are not well studied or well understood, mostly because very few worlds have been discovered in what is known as the Warm Neptune Desert.

Cooler ice giants retain their primordial hydrogen-helium envelopes with traces of methane and ammonia. At intermediate temperatures, methane becomes the dominant carbon-bearing molecule. With increasing temperatures, water becomes more prominent, because of formations rich in ice. As the temperatures increase further, carbon gases increase, shifting the chemical equilibrium, with nitrogen as a minor component.

Planets need to have immense mass to retain the lightest elements, hydrogen and helium on the surface. With increasing temperatures, these gases escape more easily into space. Cooler, heavier worlds can retain atmospheres with more hydrogen and helium, as well as more water. Sub-Neptunes or Super-Earths can potentially be Hycean Worlds, worlds with global oceans, combined with a hydrogen rich atmosphere. These worlds may be habitats for lifeforms with exotic biochemistries.

Methane formation is favoured in a carbon rich world, while water and carbon dioxide form more easily in an oxygen rich world. These worlds too, are stripped of their atmospheres in close proximity to the host stars. The rate at which the gases escapes from the atmosphere depends on how thick the hazes in the upper atmosphere are.

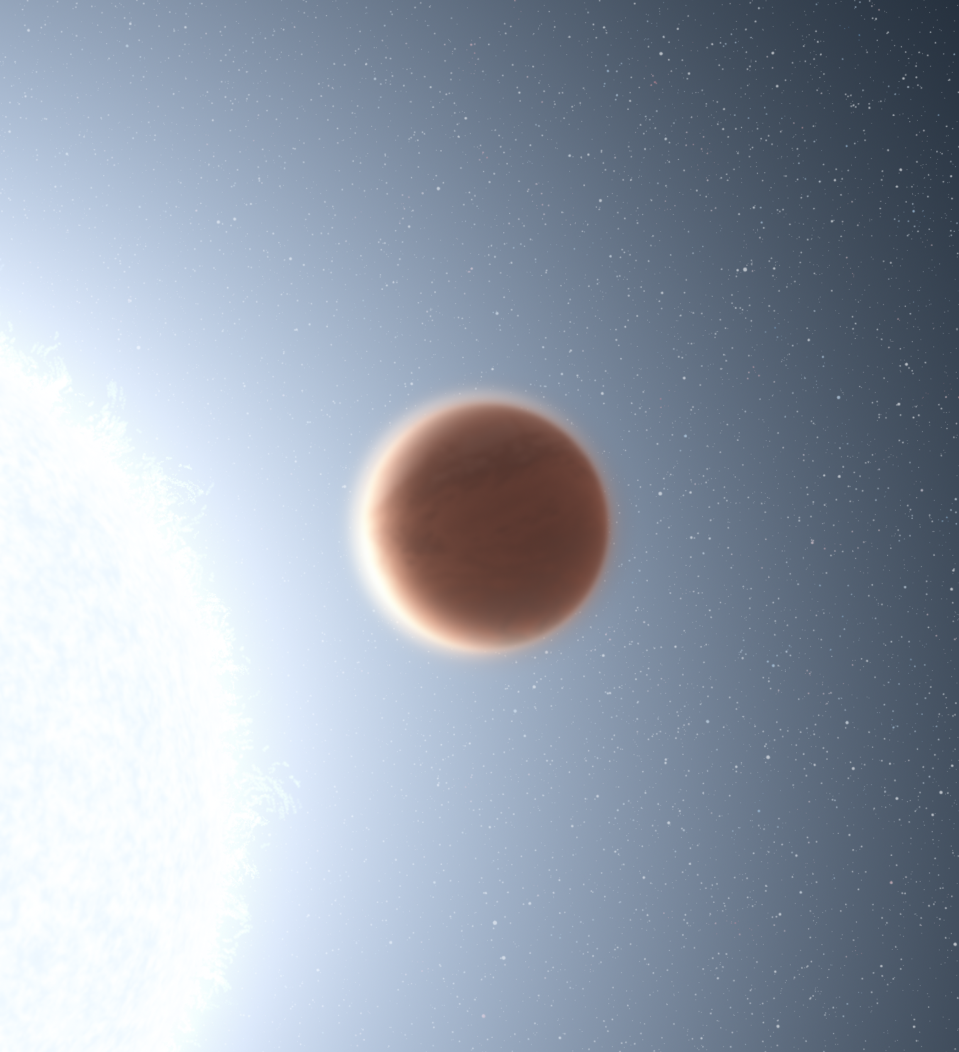

GJ 1214 b is a Warm Neptune around a Red Dwarf star, with a thick atmosphere made up of hydrogen, helium and water. Thick hazes made up of aerosols blanket the planet.

TOI-421 b is another Warm Neptune that is simply too hot for clouds to exist. Its clear atmosphere may allow light to penetrate to deeper depths, influencing the chemistry.

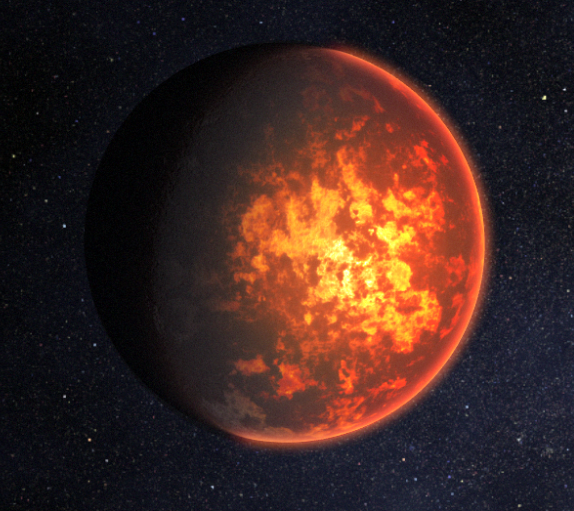

55 Canceri e is a tidally locked Super-Earth whose tenuous atmosphere is constantly being stripped. Excessive volcanism scars the airless world.

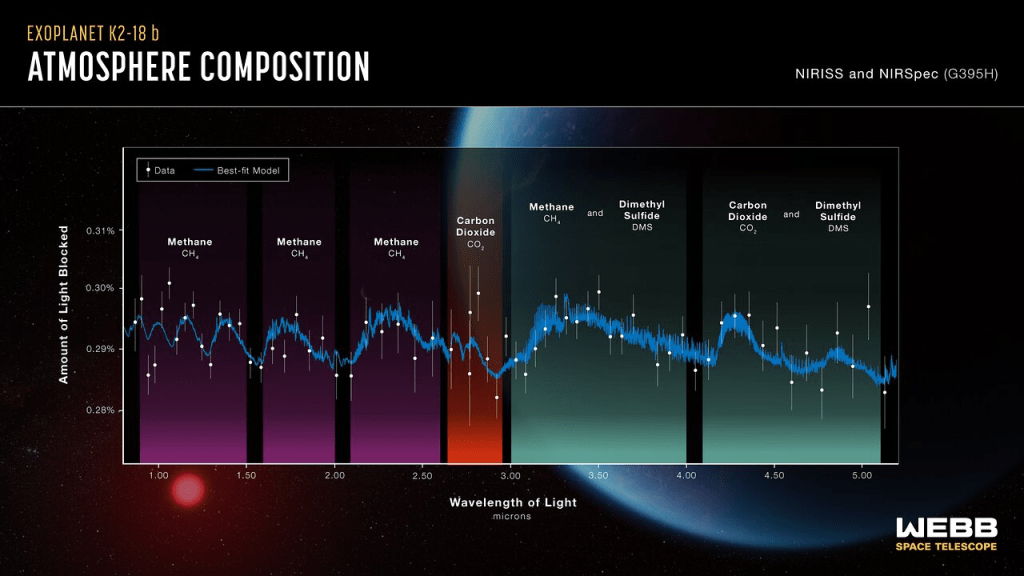

K2-18 b has an excess of carbon dioxide and methane, but very little ammonia, indicating that it hosts a water ocean in an atmosphere dominated by hydrogen.

Terrestrial Worlds

Small, rocky worlds can readily form in the inner regions of the star system, but also in the outer reaches. These terrestrial worlds have metal-rich cores, surrounding by mantles of molten rock, with a solidified surface. In the inner system, they often experience intense stellar radiation, leading to barren, hot surfaces, while those in distant orbits may host icy crusts and even subsurface oceans. Their diversity in composition and environment makes them key targets in the search for habitable conditions and signs of life beyond Earth.

Enveloping them can be a range of atmospheres, depending on the temperature and irradiation conditions. These worlds can be occupied by carbon based lifeforms, with the atmospheres shaped by both geological and biological processes. On colder worlds, atmospheres rich in nitrogen, methane, or hydrocarbons might dominate, while hotter planets could host thick layers of carbon dioxide or water vapor.

The warmer terrestrial worlds can have a runaway greenhouse effect, with a thick atmosphere trapping the heat from the host star. The more distant, cooler worlds can host hydrocarbon lakes on the surface. These worlds are rich environments for complex chemistries. Photochemical reactions could occur in the dense atmospheres of these worlds, replenishing the hazes in the sky and the inventory of materials available on the surface.

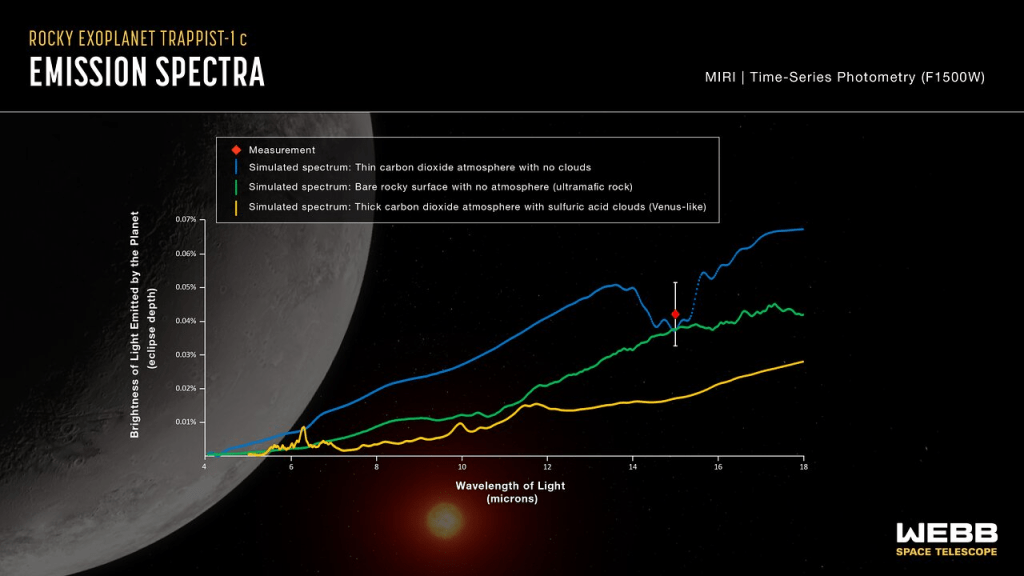

Trappist-1 is an ultracool red dwarf that hosts seven terrestrial worlds, all of which are tidally locked and in tight orbits. There may be water on these worlds.

Teegarden’s Star is orbited by a pair of small, terrestrial worlds. The red dwarf star is between eight and ten billion years old, around twice the age of the Sun.

TOI 700 hosts three rocky planets, the outermost of which is within the inner edge of the habitable zone. All the three worlds are tidally locked to the host star.

Kepler-1649 hosts a pair of worlds similar to Venus and Earth, but in orbit around a dim red dwarf star as against an orange dwarf like the Sun.

Water Worlds can have atmospheres saturated with vapour, resulting in extreme but habitable worlds. High pressures and temperatures could create a supercritical water layer, blurring the boundary between ocean and sky. These worlds could experience experience intense weather patterns, such as perpetual storms or heavy rainfall, along with ginormous tides. Stable terrestrial worlds with metallic atmospheres are unlikely to form, but a combination of unusual compositions, planetary collisions, irradiation from the host star, and atmospheric stripping could briefly create such an oddball.

Oddballs

There are a whole range of extreme worlds that can potentially exist across the cosmos. The characteristics of the atmosphere are determined by the composition of the world and where it was formed, its mass, its distance from the host star, the thickness of the hazes in the upper atmosphere, and how exposed the world is to the energies from the host star. Some planets may have corrosive clouds of sulfuric acid, while others could be shrouded in methane haze, obscuring a surface of cryovolcanoes. Others still might have atmospheres of pure hydrogen, allowing for exotic weather patterns driven by deep atmospheric convection.

There can be larger versions of Venus with a thick carbon dioxide rich atmosphere and crushing atmospheric pressures. Water Worlds with similarly crushing atmospheric pressures could host supercritical ice, that behave like liquids. A gas or ice giant at just the temperature threshold for hydrogen to escape can have an atmosphere enriched with helium. Tidally locked worlds can lead to stark contrasts between scorching daysides and frigid nightsides, while planets in binary star systems could endure erratic climate cycles due to the gravitational interplay of two stars. These factors create a staggering diversity of planetary environments

A Chthonian Planet is a gas giant that has been stripped of its outer layers entirely, leaving behind a rocky core. Larger versions of Mercury can potentially form, which would be ultra-dense, with rivers of molten iron flowing across the surface. Any inhabitants would get metal fatigue. A world that orbits its host star within its corona or outer atmosphere would perpetually be within a plasma storm. A colder version of the volcanic moon Io could have thick layers of sulphur frost. A warmer version of the ice moon Titan can be covered by thick clouds of soot and hydrocarbon smog.

Carbon Planets would have thick clouds of hydrocarbons and carbon monoxide over landscapes of graphite, tar and potentially even diamond formations.

Helium Giants are stripped of hydrogen may have thick clouds of exotic noble gases, and unusual atmospheres made up of neon and other heavy elements.

Volcano Worlds: Cold volcanic worlds in large orbits around host stars could have tenuous atmospheres, that are constantly being replaced by outgassing.

Hot Neptune: Some worlds could be at the triple point of water, with temperature and pressure conditions allowing water to simultaneously exist as ice, liquid and vapour.

Violent processes may in-fact, catalyze life. Planets might be wrapped in endless storms, with lightning arcing across their entire atmospheres, while others are locked in eternal darkness, their surfaces sculpted by frozen winds. Life would be forced to adapt in ways unimaginable—perhaps swimming through oceans of liquid methane, or clinging to the undersides of floating iron flakes in a superheated metal storm. Many of these worlds would be utterly inhospitable to life as we know it, a stark reminder that even a lifeless universe can be a place of incredible beauty and brutality.

Image Credits:

Cover Image: NASA SVS

Protoplanetary Discs: NASA, ESA, ESO, STScI, ALMA, S. Andrews (CfA), Bill Saxton (NRAO, AUI, NSF), T. Stolker (ALMA)

[CB88] 130, LDN 507: ESA/Hubble, NASA & STScI, C. Britt, T. Huard, A. Pagan

Artist’s conception of early star formation: Adolf Schaller for STScI.

WASP-39 b Atmospheric Composition (NIRSpec PRISM): NASA, ESA, CSA, J. Olmsted (STScI)

Spectra of exoplanet K2-18 b: NASA, CSA, ESA, J. Olmstead (STScI), N. Madhusudhan (Cambridge University)

TRAPPIST-1 c emission spectra: NASA, ESA, CSA, J. Olmsted (STScI), S. Zieba (MPI-A), L. Kreidberg (MPI-A)

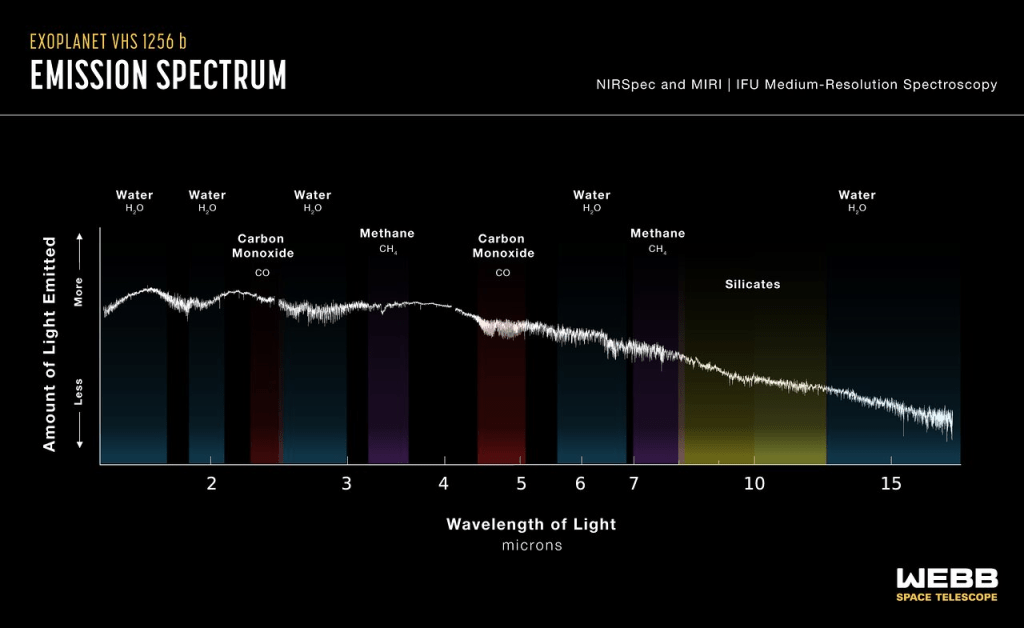

Exoplanet VHS 1256 b (NIRSpec and MIRI emission spectrum): NASA, ESA, CSA, J. Olmsted (STScI), B. Miles (University of Arizona), S. Hinkley (University of Exeter), B. Biller (University of Edinburgh), A. Skemer (University of California, Santa Cruz)

WASP-17 b Illustration: NASA, ESA, CSA, and R. Crawford (STScI)

Artist’s impression of the night side of WASP-76 b: ESO/M. Kornmesser/L. Calçada

Artist’s impression of supersonic winds on WASP-127b: ESO/L. Calçada

Illustration of KELT-20b: NASA, ESA, Leah Hustak (STScI)

Gas Giants at different compositions and temperatures: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/V. Parmentier

The Warm Neptune Desert: NASA, ESA and A. Feild (STScI)

55 Canceri e: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Artist Concept-Exoplanet K2-18 b: NASA, CSA, ESA, J. Olmsted (STScI), Science: N. Madhusudhan (Cambridge University)

TRAPPIST-1: ESO/M. Kornmesser

Water World: ESA

Earth-like Exoplanet: ESA. Illustration by Medialab

Illustration of 55 Canceri e: NASA, ESA, CSA, Dani Player (STScI)

GJ 436 b: NASA

Artist Impression of the exoplanet WASP-76b: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva/Spaceengine/M. Zamani

Illustration of Kepler 138: NASA, ESA, L. Hustak (STScI)

TOI 700d: NASA GSFC

Teegarden’s Star: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Kepler-1649c: NASA/Ames Research Center/Daniel Rutter

Leave a reply to satyam rastogi Cancel reply