As the James Webb Space Telescope turned its sensitive infrared gaze towards various deep space targets, astronomers discovered something remarkable in the background, distant galaxies from the dawn of time. These enigmatic objects known as Little Red Dots (LRDs) are mysterious and intriguing, mostly because nobody expected them to exist so soon after the Big Bang. These compact, high-redshift sources have puzzled scientists, challenging long-held theories about galaxy formation, black hole growth, and the evolution of the early universe. Their deep red hue, unique spectral properties, and apparent abundance make them one of the most fascinating finds of modern astrophysics.

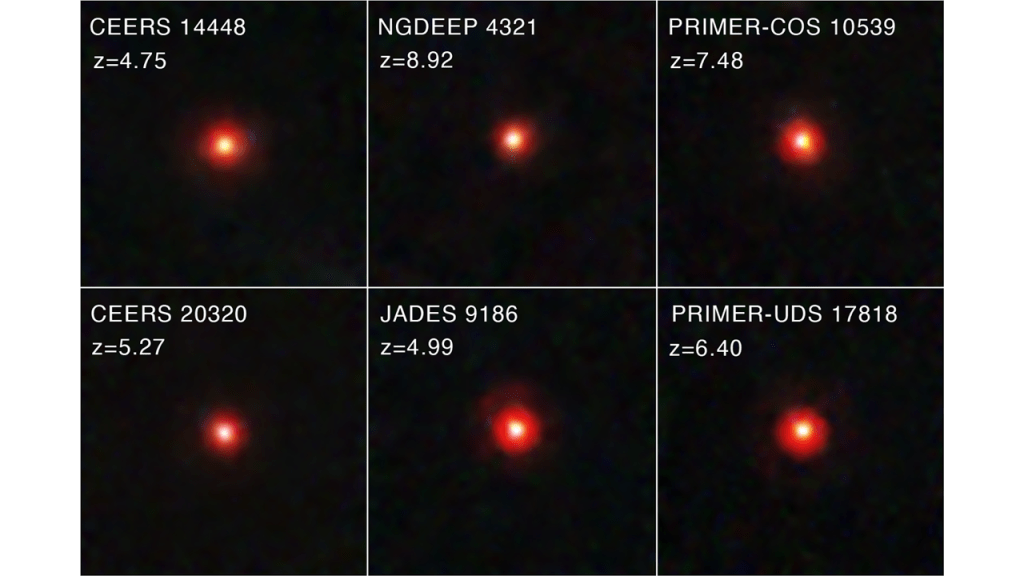

Little Red Dots spotted by Webb. The cover image is JADES 9186. The ‘z’ is a measurement of the red shift. NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, D. Kocevski (Colby College)

The defining characteristic of LRDs is their deep red color. This redness carries essential information about their nature and distance. The further an object is in the universe, the more its light is stretched by the expanding cosmos, shifting it into the red part of the spectrum. LRDs are found in unexpected abundance at a time when the universe was only a fraction of its current age.

Despite their small size—ranging from just 500 to 1,000 lightyears in radius—LRDs radiate with remarkable intensity. The Milky Way for example, measures 52,850 lightyears across. The spectral energy distribution (SED) of LRDs follow a peculiar pattern: a “V-shaped” curve where a steep red optical slope suddenly transitions into a blue ultraviolet slope. This transition, occurring near the so-called Balmer limit around 3500-3645 Å, hints at complex underlying physical processes, possibly linked to the presence of accreting black holes or extreme stellar populations.

Ghostly Giants in Abundance

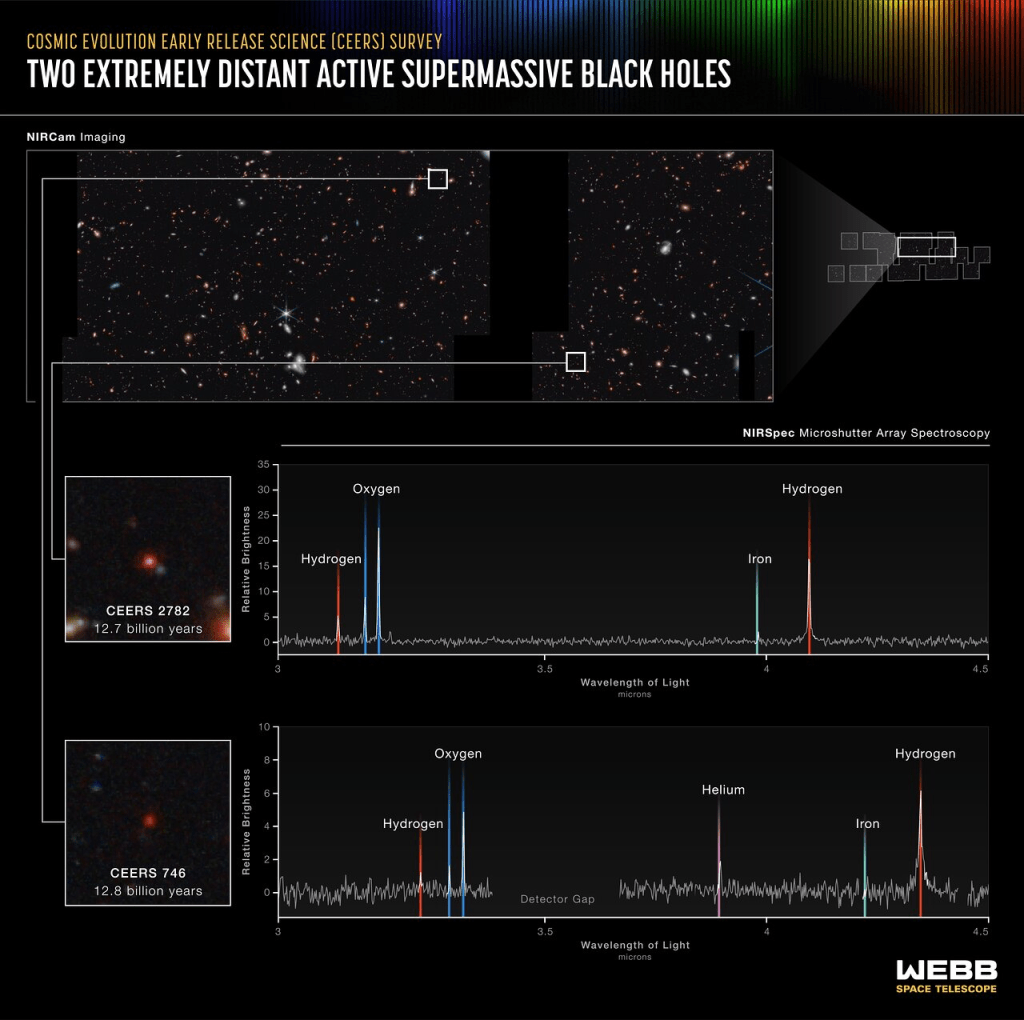

One of the most tantalizing clues about LRDs is their potential link to active galactic nuclei (AGNs), the luminous centres of galaxies powered by supermassive black holes. Spectroscopic analysis reveals that over 70% of LRDs exhibit broad hydrogen Balmer lines—one of the hallmarks of AGN activity. Yet, unlike most known AGNs, many LRDs appear strikingly faint in X-ray wavelengths. This puzzling characteristic defies conventional models, which predict that accreting black holes should be powerful X-ray emitters. What could be muting their high-energy signatures? Are LRDs shrouded in thick clouds of gas and dust, or are they powered by an entirely new mechanism of black hole growth?

The number of LRDs detected by JWST far exceeds what previous models predicted for high-redshift AGNs. Their estimated density is high considering the universe was only around for less than half a billion years, suggests that whatever process is generating these objects must have been highly efficient in the early universe. This newfound abundance raises fresh questions about how supermassive black holes formed and grew in the first billion years after the Big Bang.

Several theories have emerged to explain the nature of LRDs. One possibility is that they are powered by accreting primordial black holes—ancient remnants of the universe’s first gravitational collapses. Another hypothesis suggests that they could be tidal disruption events, where runaway-collapsing star clusters feed black holes at an extreme rate. These ideas are still being tested, and as more JWST data pours in, astronomers are racing to determine which, if any, of these explanations holds true.

Understanding the host galaxies of LRDs adds another layer of difficulty. Their compactness makes it challenging to separate the emission of the AGN from that of the surrounding galaxy. Are they nestled within small but rapidly evolving galaxies, or do they represent a fundamentally different type of celestial object? Deciphering this mystery is crucial for piecing together the history of the early universe.

A Cosmic Time Machine

The study of LRDs is more than just a quest to classify new celestial objects—it is a journey into the past. These distant sources provide a unique opportunity to probe the infancy of galaxies and the early growth of black holes. Their high luminosities and unexpected abundance challenge standard cosmological models, particularly those based on the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM) framework, which describes how structure formed in the universe over time.

Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Leah Hustak (STScI), S. Finkelstein (UT Austin), R. Larson (UT Austin), P. Arrabal Haro (NSF’s NOIRLab)

Moreover, LRDs offer insights into the role of dust and obscuration in AGN activity. If they represent a population of dust-reddened quasars, they could help bridge the gap between heavily obscured and unobscured AGNs, shedding light on the processes that govern black hole feeding and feedback in the universe’s earliest epochs.

Beyond the Red Horizon

Despite their apparent ubiquity, LRDs contribute only a negligible fraction—about 0.1%—to the cosmic dust budget at redshifts greater than four. This suggests that while they are numerous, they do not play a major role in the enrichment of the intergalactic medium with heavy elements. Their influence on the cosmic landscape remains an open question, but one that JWST and future telescopes will continue to explore in the coming years.

As astronomers sift through the ever-growing JWST datasets, the story of the Little Red Dots is far from over. Each new observation peels back another layer of cosmic history, revealing a universe that is even more intricate and surprising than we ever imagined. Whether they are the fingerprints of primordial black holes, echoes of ancient stellar cataclysms, or something entirely unexpected, LRDs remind us that the universe still holds secrets waiting to be uncovered.

Sources / Further Reading

Evaluating the Predictive Capacity of FLARES Simulations for High Redshift “Little Red Dots”

Accretion onto a Supermassive Black Hole Binary before Merger

Sub-Eddington accreting supermassive primordial black holes explain Little Red Dots

Halo mergers enhance the growth of massive black hole seeds

Little Red Dots are Tidal Disruption Events in Runaway-Collapsing Clusters

Deep silence: radio properties of little red dots

Discovery of dual “little red dots” indicates excess clustering on kilo-parsec scales

Leave a reply to Dark Stars – StarBullet.in Cancel reply