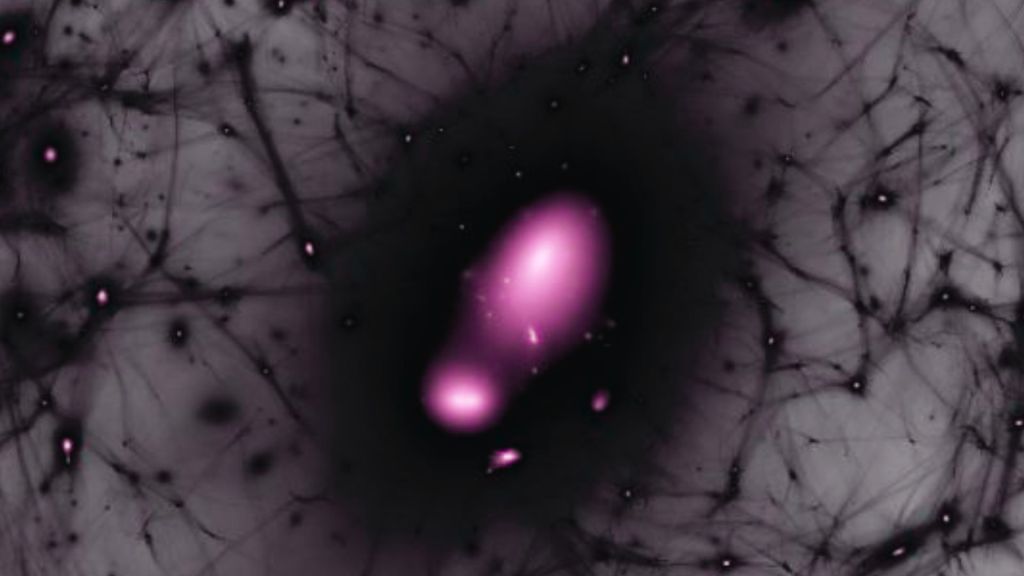

Haloes of galaxies extend well beyond the visible disk of stars. Galaxies are the visible nuclei of these vast, roughly spherical haloes that extend between 10 and 20 times the size of the galaxies. These galaxy haloes are made up of gas as well as dark matter, with the mysterious invisible substance allowing galaxies to maintain their shapes. Without the influence of the dark gravity from dark matter, all the stars in galaxies would fly out and scatter. The gas within these galaxy haloes is called the circumgalactic medium, or CGM. It mediates the exchange of gas and dust in and out of the galaxies, the raw material from which stars are formed. The material between the galaxy haloes is called the intergalactic medium, or IGM, which holds most of the hot gas in the universe.

Scientists are puzzled by warm ions in the gas, which are charged atoms. O VI is oxygen with six electrons stripped. Such ions absorb specific wavelengths of light from distant sources, such as quasi-stellar objects or quasars, distant galaxies with actively feeding black holes in their cores, that appear as point sources of light, similar to stars. The warm ions in space absorb wavelengths of light from quasars, which have been investigated in multiple astronomical surveys. The signature of ionised oxygen has been detected out to 400 kiloparsecs from galaxies, with no sharp drop-off, with low-mass galaxies showing signs of ionised oxygen even further out, up to 1,000 kiloparsecs.

A 1D model of the universe

Itai Bromberg and colleagues have built a simple model to explore galaxy haloes. They tracked dark matter haloes as they collapse under gravity. Haloes start off as small overdensities in the early universe. These dense knots of gas cause more gas to fall in, that heat up at a shock front, and reach virial temperatures. What this means that the random motions powered by thermal energy or temperature of the gas support it against the collapse due to gravity, just like the pressure in a balloon maintains the shape. This matches the specific temperature where the speed of the atoms or molecules in the gas halo matches the speed needed to orbit or stay bound in the gravity well of the halo. The researchers developed a one dimensional model to explore galaxy haloes.

The model follows 1,000 shells of dark matter from a redshift of 100 to today. Each shell traces a path in an expanding universe. Baryons, or the regular matter that we can see, follows dark matter at 16.5 per cent density. Inside the haloes, gas heats to virial temperatures. Collisions strip electrons and make ions. Outside the haloes, in the intergalactic medium, gravity from the halo pulls gas. This gas remains cooler and is ionised by the ultraviolet light from distant quasars and stars. The important thing to understand here is that one type of chemistry occurs in the warm gas within the haloes, with photochemistry occurring in the cold gas falling in to the haloes. The team used a software called Cloudy to calculate ion fractions, assuming 0.1 solar metallicity in the circumgalactic medium, and 0.03 in the intergalactic medium, which are the levels actually observed.

Metallicity here refers to how evolved or polluted the material is. The early universe only had pristine clouds of hydrogen and helium, with trace amounts of lithium beryllium, these are in order, the lightest elements. All elements other than hydrogen and helium are considered metals by astronomers. These metals such as carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and silicon were all cooked by the nuclear furnaces inside stars, by fusing atomic nuclei into progressively metallic elements. The metallicity here refers to the amount of enrichment in the matter, and is necessary for the ionised gas. Within the intergalactic medium, density increases close to the haloes, that boost photoionisation. This creates a thick layer of ionised oxygen around he circumgalactic medium, up to three megaparsecs out. In the simulations, the intergalactic medium provides half of the ionised oxygen seen in the galaxy haloes.

The 1D model match with the observations, as well as roughly with more sophisticated simulations of the universe based on the conventional understanding of science. If the galaxy is more metallic, it increases the density of the oxygen as well. As the temperature and density inside the shocked circumgalactic medium is dependent on the virial temperature and gravity of the halo, this is a simple multiplication. In the intergalactic medium, the process is a bit more complex. Metals radiate energy more easily, and the intergalactic medium cools a bit, this small shift in temperature means that the density of ionised oxygen rises almost linearly with metallicity, but not exactly 1:1. The slight cooling effect shifts how many atoms are ionised, termed the ion fraction.

The Warning

The scientists also warn of an assumption that may be preventing scientists from understanding the universe. Scientists have used warm ions to study streams of gas flowing into galaxies, stellar winds blowing gas out of galaxies, feedback from newborn stars or actively feeding black holes, and the temperatures of gases. If you are investigating all these physical processes based on observations along a single line of sight from a distant light source, such as a quasar, than all the stuff along the entire line of sight, the tenuous, wispy, cold gases in the intergalactic medium, may muddy the conclusions. A large part of what we see, often most of it, especially at larger distances, or around lower-mass galaxies comes from photoionised intergalactic gas pulled denser by the gravity of the halo, not from the processes inside the circumgalactic halo.

The small, dwarf galaxies do not form stable haloes, and in theory should not form any ionised oxygen. So any ionised oxygen detected in their haloes, must come from intergalactic gas. The scientists have highlighted the need for more sophisticated 3D hydrodynamic models, better-understood cosmology, and the use of local UV sources in addition to distant quasars, to fully understand the processes at work in the circumgalactic haloes, how it controls the flow of gas, how it links up to the cosmic web, and mediates the process of star formation in galaxies. The intergalactic medium creates a ‘blanket’ contamination. This warning may transform how scientists study the haloes of galaxies.

A large part of the metals attributed to the circumgalactic medium around foreground galaxies in the Lyman Alpha Forest actually came from enriched intergalactic medium gas in filaments or voids, polluted by galactic outflows over cosmic time. Any quasar sightline probing galaxy environments risks blanketing by the intergalactic medium, particularly for warm photoionised ions with density enhancement without shocks near haloes. Intergalactic medium contamination is now recognised as a systemic issue in absorption-line astronomy, which is why we need the more sophisticated compute.

Cover Image: Ralf Kaehler/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Leave a comment