Ancient scepticism regarding the nature of reality, as described by Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and the ‘evil demon’ of Descartes was revived, popularised and crystallised in contemporary thought by the ‘Simulation Argument’ of Nick Bostrom in the seminal 2003 paper Are You Living in a Computer Simulation? The theoretical grounding was actually provided nearly a decade earlier. In 1994, Leonard Susskin and Gerard ‘t Hooft proposed something that sounds completely backwards at first. They argued that the three-dimensional world, the space that we live in, our mountains and undersea trenches are all just an image. Physical reality as we experience it is a projection of information that is stored on a two-dimensional space. You may experience everything around you in 3D, but it is actually sitting on a 2D wall somewhere at the edge of space.

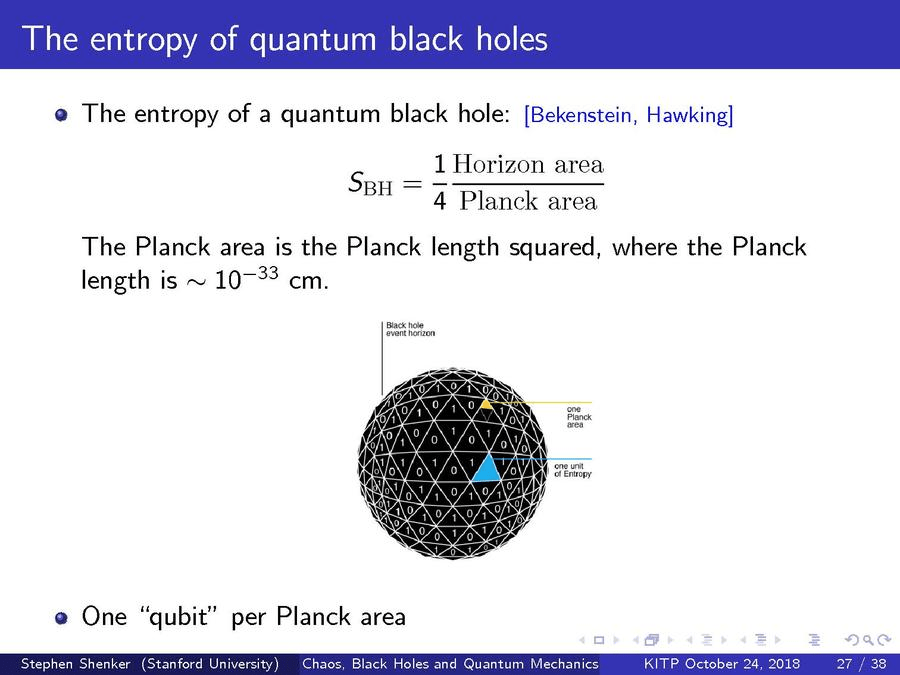

Qubits are the pixels of reality. (Image credit: Stephen Shenker, Stanford Univ. & KITP 27)

If you imagine a can of soup, the soup is inside the can, but it is possible to describe all the contents mathematically on the label. The soup inside can just be a 3D projection of the label. this is known as the holographic principle. If reality is that can of soup, then there is a limit to how much soup the universe can hold. When viewed at the finest-grain, the pixel of reality is something called the Planck Area, the smallest possible or quantised unit of area in the universe. This is the square of the Planck Length, the scale where quantum mechanics and special relativity interact, and where known physical laws break down. No measurement in physics can be smaller than this scale.

The holographic principle

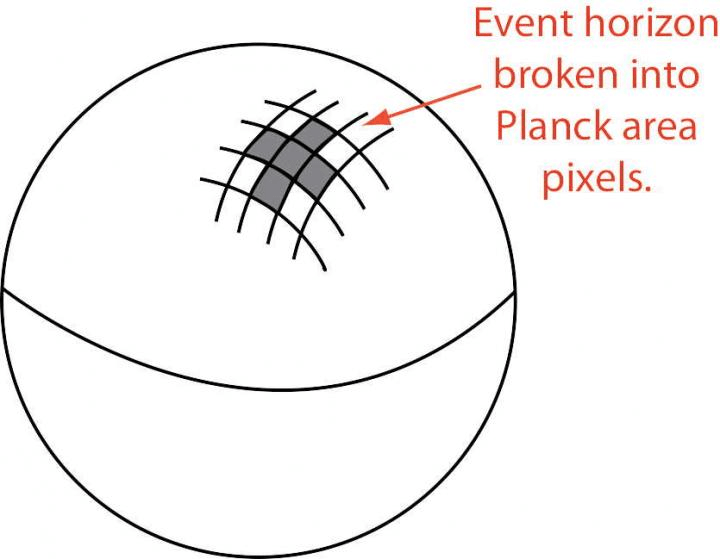

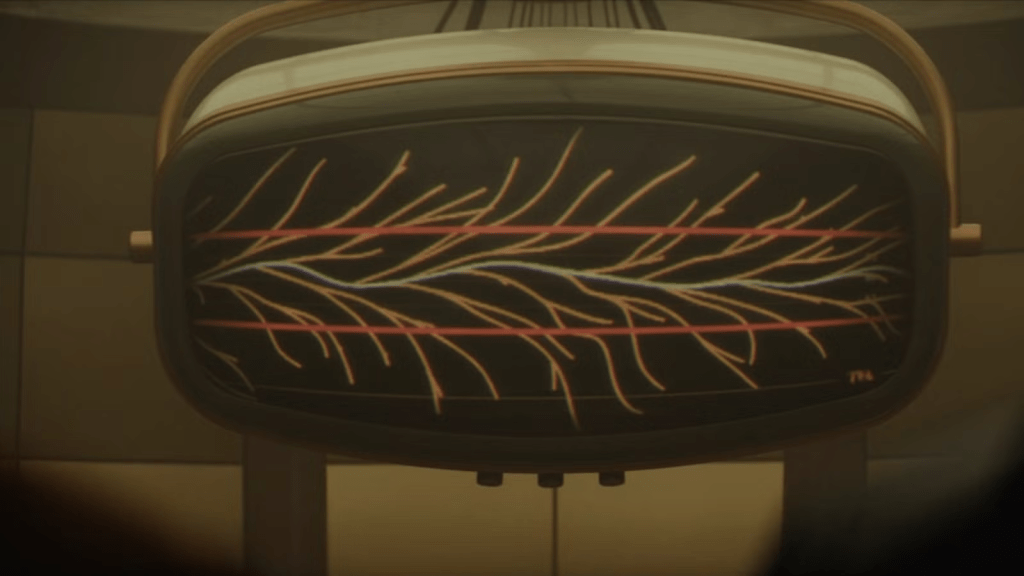

According to the theory, you get one bit of quantum information per Planck Area. So, reality is not a smooth continuum but a 2D grid of bits, or pixels projected inwards. Where it gets really interesting is that black holes may provide us with direct evidence of the Holographic Principle. If you have a box, the amount of stuff you can put in it grows with the volume of the box. A bigger box can accommodate more stuff. But black holes do not work that way. The information that a black hole can contain is not proportional to its volume, but to the surface area of the event horizon. If you throw a book into a black hole, it does not disappear into a 3D ball, but spaghettifies and gets smeared across a 2D surface. Susskin describes the event horizon as a screen, and compares it to an incompressible fluid. Matter falling into the event horizon spreads out, because it cannot be compressed into less than one bit per Planck Area. All the matter in the universe reduces to the smallest bits on encountering the event horizon, where it piles up, much like sedimentary deposits under flowing water. All of this makes the Simulation Hypothesis more likely.

The event horizon is broken up into Planck Area pixels. (Image Credit: Yan-Gang Miao & Zhen-Ming Xu).

Physics tells us that reality handles information like a 2D surface. That sounds like a computer rendering engine optimising for memory. It opens the door to to the ‘It from Bit’ idea, that the fundamental thing is not matter, it is information. If the universe is information being processed, then someone is doing the processing. In 2023, Evangelos Katsamakas approached the problem from a fresh angle. Instead of exploring if a simulated universe is possible, he asked what is the return on investment? As existing literature lacked a specific term for a universe consistent with the Simulation Hypothesis, Evangelos Katsamakas proposed ‘Simuverse’ in 2004. A simuverse relies on information processing, and is aligned with the concept of ‘It from Bits’, which posits that every physical quantity is ultimately derived from binary bits of information. In this view, information is the fundamental building block of reality, with matter being secondary.

Simulation as a Service

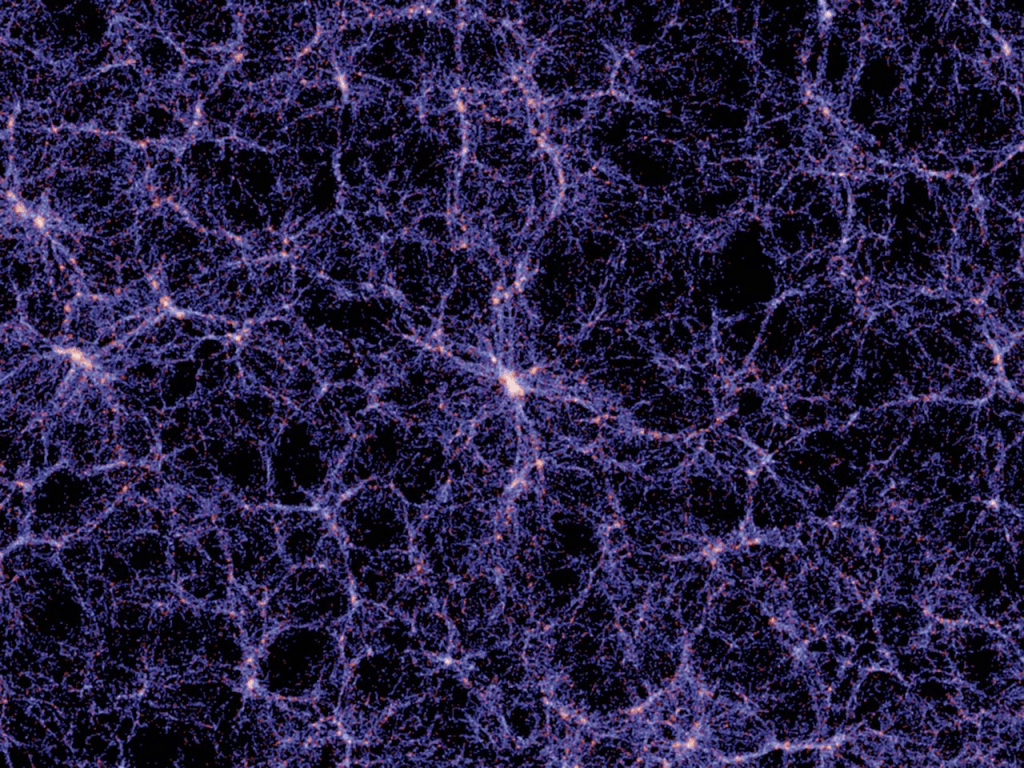

A universe can be pretty high maintenance, so anyone running a simulation would require a strong enough economic incentive to do it. Let us say an advanced civilisation has undertaken operating such a simulation. Scenarios for justifying the costs include a project, for internal research or education, a service, where less-advanced client simulation pays for access, or a platform that facilitates interactions between multiple groups. In simple words, technologically sophisticated aliens can offer simulated universes as subscription services, that can potentially function as a social network as well. It is possible for the universe to contain a computer that simulates the universe itself, with multiple identical instances of the same reality in the self-simulation, all equally real, and existing in an infinite regress of nested simulations.

Scientists do simulate the universe. (Image Credit: Springel et al., 2005).

Even if you are a near omnipotent civilisation tapping into the energy outputs of entire galaxy clusters, you will still have a budget, and be constrained by resources. Even gods have accountants. Advanced civilisations would not run these massive energy-sucking simulations without an incentive, something that justifies the investment. One of the humbling options is that our universe is just training AI models of the creators. Another option is that Reality is a SaaS product, with God being a service provider, and clients paying fees to access the services. For a few extra bucks a month, you may get to live in Earth Premium Plus, without the climate change and the humans with dusty heads. Such systems would benefit from economies of scale. Maybe the physics that we experience are just the standard-tier features, and you can pay a premium to unlock faster than light travel. The third model is the Simuverse as a platform, a two-sided market with the provider building and maintaining the infrastructure, such as the periodic table or the laws of physics, and then third party creators make the content.

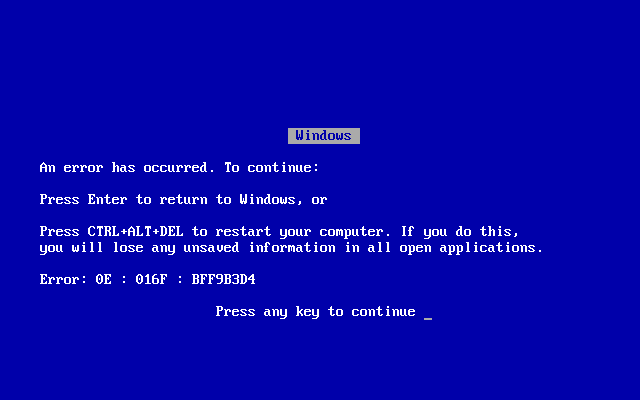

Does the universe have a BSOD? (Image Credit: Akhristov).

One chilling idea proposed by Preston Greene is that if the universe is in-fact a simulation, it might not be such a great idea to test the limits of the system or prod around the corners of reality too much. If we do something that breaks the system, then the universe could glitch, or reboot. Reckless experiments to test the simulation hypothesis could potentially result in the termination of the universe itself. This leads to some terrifying termination risks.

Existential Dread

If the universe is a business, it can go out of business. Software bugs, hardware failure, or something as mundane as budget cuts can result in the lights of the universal projector being switched off. The Q4 earnings are down, we have to delete the Milky Way. The owner could sell our data to malicious third parties. Our entire existence may be harvested for behavioural analytics. Physics supports a holographic universe that is built on pure data, an economic reason for someone to build it, but Mir Faizal, Lawrence M Krauss, Arshid Shabir and Francesco Marino try to ruin the party, or save us from the existential dread, depending on which way you look at it.

Something like the Time Variance Authority might be needed to keep the universe in line. (Image Credit: Marvel).

Their whole argument is that a simulated universe is essentially impossible. A computer simulation has to be algorithmic. It has to follow rules. But they argue, that our universe contains phenomena that are undecidable. There are just some things that we can see and experience, that cannot be solved by algorithms. They pull in a triad of logical limits, fist Kurt Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem that demonstrates that any consistent formal system contains true statements that cannot be proven, Alfred Tarski’s Undefinability Theorem that proves that a system cannot be defined using language of that same system, and Gregory Chaitin’s Information-Theoretic Incompleteness Theorem, that limits the complexity of a problem that can be solved, implying that there are mathematical truths of higher complexity than the universe can produce or solve.

The Meta-Theory of Everything

A cup of coffee cooling off is an example of thermalisation of a system. How exactly this happens in some quantum systems is mathematically impossible to predict or model. It is not just hard, an algorithm just cannot do it. If the universe has things happening in it that are not algorithmic, then the universe itself cannot be an algorithm. A standard computer or a Turing Machine would hang, it would enter an infinite loop trying to solve the undecidable parts. If the universe were to be a simulation, then a cup of coffee can crash it. To understand the universe, there is a requirement for a Meta-Theory of Everything, something that suggests that reality is more than just bits. This can be reassuring, at least to those worried about the universe simulation running out of funds, or worse, a encountering an unexpected power cut.

Is VR chair real? (Image Credit: Meta4Space).

David J Chalmers has proposed that say a chair that we experience in a simulated universe is as real as a chair in meatspace. Chalmers argues that the difference is a metaphysical one, and not an illusory one. In a physical universe, the chair would be made of quantum fields. In a simulated universe, it would be made of quantum bits, or qubits. In both cases, the chair exists. You can sit on it, it holds you up, it has causal power in its reality. Even in a simulated universe, the chair is real, it is just that it is made up of digital code instead of quarks. We should not really care about the substrate at all, whatever the universe is made up of, our experiences within it are genuine. Love, achievement, value… all of that persists. This approach validates ours existence independently of the substrate. Life in a simulated universe is just as good as life in a physical one.

Cover Image: NASA SVS

Leave a comment