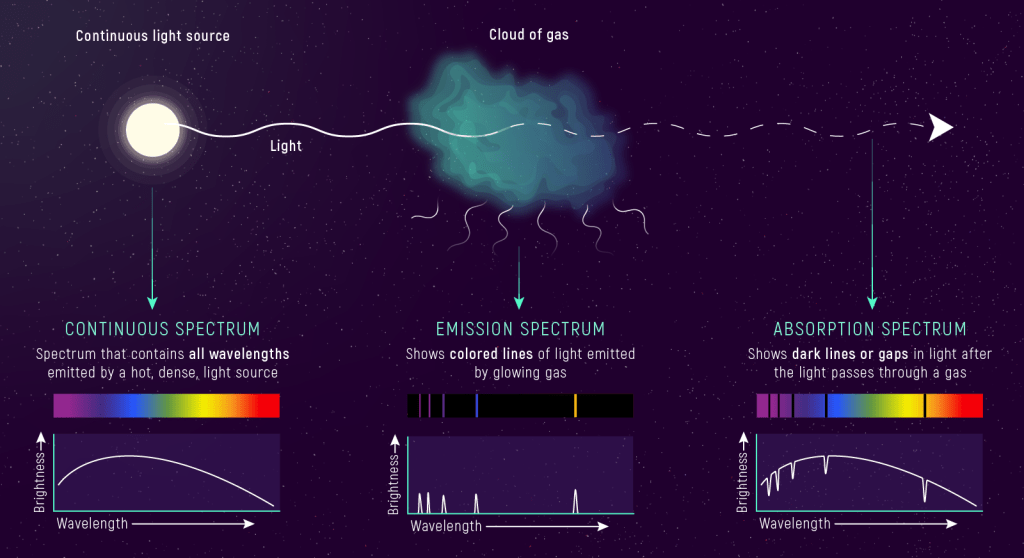

Spectra are charts that show the intensity of light at different wavelengths. Just like a prism splits sunlight to form a rainbow, light from distant astronomical objects of interest can be spread out to form a spectra. Astronomers can examine the spectra to determine the composition of objects, along with their temperature and motion. There are three main types of spectra, a continuous spectrum shows all wavelengths of light, like a rainbow. Such light comes from hot, dense objects such as filaments in lightbulbs or stars. An emission spectrum has bright lines at specific wavelengths, or colours, on a dark background. An absorption spectrum is a continuous spectrum with dark lines at specific wavelengths. These dark lines are where light is missing, because it was absorbed by cooler gas.

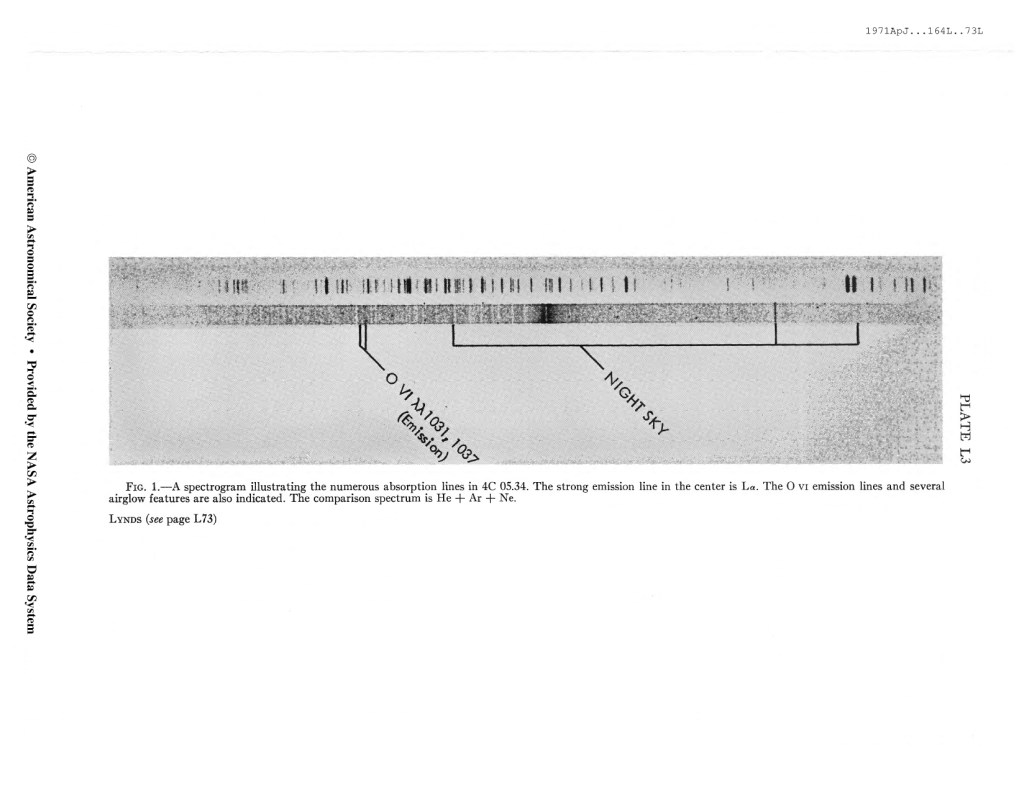

The Lyman Alpha Forest shows up in the form of a forest of dark lines in the spectra of quasars, these are distant galaxies with actively feeding supermassive black holes in their cores. These lines come from clouds of hydrogen gas in space absorbing some of the light from the energetic hearts of distant galaxies. In 1970, the American astronomer Roger Lynds observed the quasar 4C 05.34. At that time, it was the most distant object known. He discovered many absorption lines in its spectrum. He thought they all came from the same kind of hydrogen transition. Other astronomers checked his work and agreed that the lines were odd, but no one understood why. More quasars showed the same pattern. Lynd called it the Lyman Alpha Forest. The Dutch astronomer Jan Oort who discovered the Oort Cloud, proposed that the lines came from dust clouds in space, not the quasars themselves.

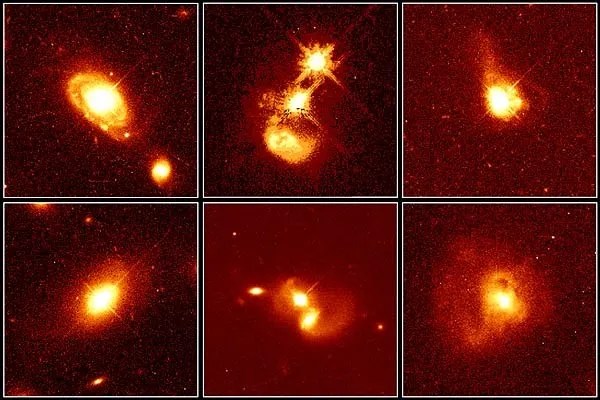

Quasars or QSOs

Quasi-stellar radio sources or objects, resemble stars when observed through ground-based telescopes, but are actually very distant, energetic galaxies.

The name comes from the Lyman Alpha line. This is a specific wavelength of light in the ultraviolet range. The physics behind its appearance is well-understood. The quasar spits out energetic photons. An electron in a hydrogen atom is usually in the lowest possible energy levels, orbiting close to the nucleus, known as the ground state. When a hydrogen atom absorbs the photon, the electron gets kicked up to a higher orbit. It cannot stay there very long, and falls back to the lower orbit, squeezing out the photon. The photon then shoots off in a random direction. This light does not reach the Earth. About 75 per cent of the baryonic mass in the universe is hydrogen. The light from a distant quasar passes through many clouds of hydrogen, with each cloud absorbing light in the Lyman Alpha wavelength.

The clouds are at different distances. As the universe is expanding, the light from the distant object gets increasingly stretched out. This is called a redshift. Each cloud the light encounters on the way, shifts the absorption line to a different wavelength. When the light is finally examined by an astronomer, they see a ‘forest’ of lines, not just one. The lines are clustered close together in the blue part of the spectrum. These hydrogen clouds are part of the intergalactic medium, the network of tenuous gas between galaxies. At higher redshifts, it is mostly neutral hydrogen, the pristine gas from the infancy of the universe. The forest here refers to not just the absorption lines in the spectrum, but the web of gas itself. The absorption lines in the spectra tells us about the density, temperature and speed of this gas, with denser clouds making stronger lines. The forest reveals the structure of the universe on large scales.

The Cosmic Web

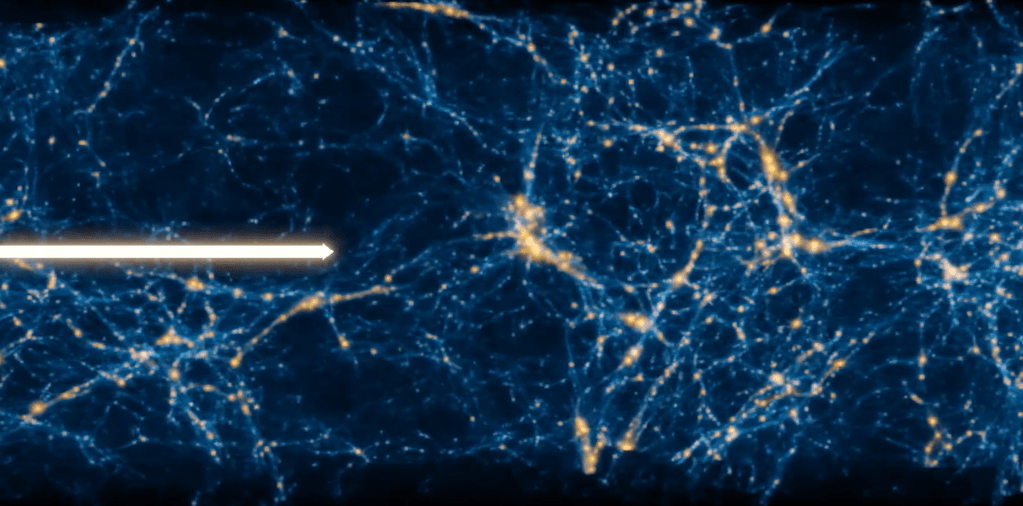

When the distribution of the intergalactic gas clouds are mapped, they reveal essentially how matter is distributed throughout the universe. While the amount of hydrogen tracks closely with the clustering of galaxies, the clouds are far more diffused than the galaxies. This suggests that the Lyman Alpha Forest closely tracks to the distribution of dark matter in the universe. Imagine you are on a mountain, that is enshrouded by fog. You have a friend somewhere, out in the distance, with a very powerful spotlight. You can map out the density and distribution of the fog by carefully examining the light. In this analogy, the friend here is the quasar, and the fog is made of hydrogen gas. Where the gas is thick or thin mirrors the distribution of how familiar stuff such as stars and galaxies, as well as invisible dark matter make up the universe. It reveals a web-like pattern, vast filaments of matter stretching like cosmic highways, connecting clusters of galaxies, with empty voids in between. This map explains how the universe grew from a homogenous, smooth soup after the Big Bang into the lumpy universe we see today. Here is a visualisation of the large-scale structure of the universe, with the white arrow showing the line of sight of the Lyman Alpha Forest.

In the standard ΛCDM model of cosmology, dark matter is cool and sluggish, allowing it to accumulate in small or large clumps over time, which matches what we see in the absorption patterns of quasars. However, if dark matter were warm or speedy, it would smooth out these tiny clumps too much, making the forest look different with fewer denser spots earlier on in the universe. The Lyman Alpha Forest rules out versions of theories that propose warm dark matter, as they are too lightweight, confirming the primary theoretical idea of dark matter, and constraining some challenging notions. Any kind of warm dark matter, including sterile neutrinos would have knocked out the smallest trees in the forest. The Lyman Alpha Forest rules out heavier neutrinos and fuzzy axions or ultra-light dark matter, both of which would have made the universe less clumpy and more smooth. The observations also rule out self-interacting dark matter, that would result in inflated or fluffy regions of high density, with the smaller clumps disappearing. The distribution of matter in the universe also indicates that dark matter is stable, and it does not heat up the gas by decaying or annihilating.

First Light

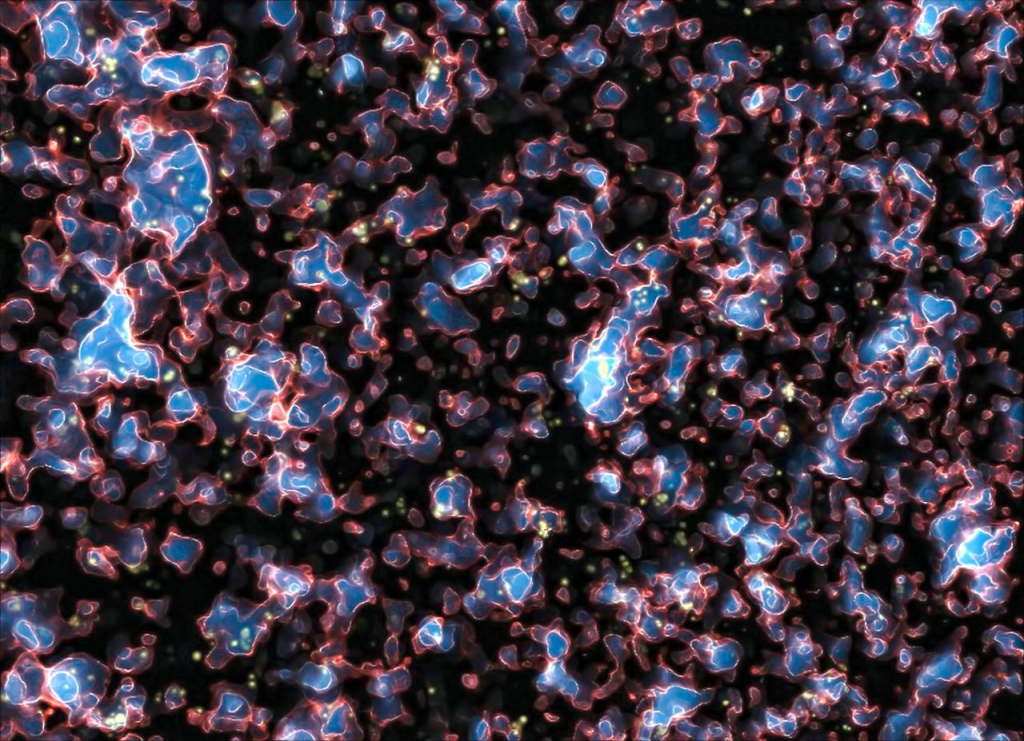

The early universe was full of hydrogen, and little of anything else. This was a cloud of neutral hydrogen, making the universe a dark place. When the first energetic stars shone with intense ultraviolet light, they reionised the surrounding gas, rendering the universe transparent. This is known as the Epoch of Reionisation. A specific and mysterious type of light pierced this darkness… these are the Lyman-alpha emissions, and the objects that produce this light are known as Lyman-Alpha Emitters (LAEs). Astronomers have discovered Lyman-alpha emissions from prior to the Epoch of Reionisation. No one knows where this light comes from, but scientists have advanced a theory, based on the exquisitely sensitive observations by the James Webb Space telescope. They say that the Lyman-Alpha Emitters are the first merging galaxies in the universe, that created bubbles and channels of ionised hydrogen, which allowed the Lyman-alpha emissions to penetrate the neutral fog. Shown below is a simulation of early galaxies ionising hydrogen gas, represented by the bright areas.

The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) is conducting the largest survey of the expansion history of the universe. The Lyman Alpha Forest has become the most powerful tool for the survey to peer into the dawn of time, where the first galaxies are too faint to see clearly. In October 2024, scientists announced that DESI observations indicated that the Epoch of Reionisation stopped about 350 million years sooner than the value predicted by cosmological simulations of one billion years after the Big Bang. Instead of mapping individual galaxies, the Lyman Alpha Forest allows DESI to map the density of intergalactic gas at high redshifts. This indicates a ‘tension’, that something is wrong in the conventional understanding of the evolution of the universe, and potentially hits at novel physics beyond the standard model.

Image Credits:

Spectra: NASA, ESA, CSA, Leah Hustak (STScI)

Quasars: John Bahcall (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton), Mike Disney (University of Wales), and NASA

Lyman Alpha Forest sightline: UCR/Ming-Feng H

Galaxies in the Era of Reionisation: M. Alvarez, R. Kaehler, and T. Abel/ESO

Sources:

The Absorption-Line Spectrum of 4c 05.34

Large-scale structure in the Lyman-alpha forest — A new technique

Cosmological constraints from the eBOSS Lyman-α forest using the PRIYA simulations

Constraints on Neutrino Physics from DESI DR2 BAO and DR1 Full Shape

Leave a comment