The Helix Nebula, designated as NGC 7293, is a planetary nebula at a distance of 650 light years from the Earth in the constellation of Aquarius. It was formed when a Sun-like star ran out of nuclear fuel, and violently shed its outer layers. The intense ultraviolet radiation from the remnant core of the dead star has ionised the shed material. The Helix Nebula, along with other planetary nebulae, are glowing shells of gas and dust expelled in the final stages of the life cycles of intermediate-mass stars. They have nothing to do with planets, that is just a misnomer that has stuck around for historical reasons. They appear as worlds when viewed using primitive telescopes. The German astronomer Karl Ludwig Harding discovered the Helix Nebula in 1823. The ejecta spans about three lightyears across. It is a well-studied nebula, a favourite among amateur astronomers because of its proximity, and has been dubbed the ‘Eye of God’.

Once the progenitor star had exhausted its nuclear fuel, it expanded into a red giant, shedding its outer envelope in multiple episodes. The inner disk formed around 6,600 years ago, expanding at a higher velocity, while the outer ring dates to about 12,000 years ago. The central star is now a hot white dwarf, packing in about as much mass as the Sun within an object about the size of the Earth. It emits intense UV radiation that ionises the surrounding gas. The ejections are asymmetric, suggesting that the progenitor star was part of a binary system. This interpretation is supported by X-ray observations.

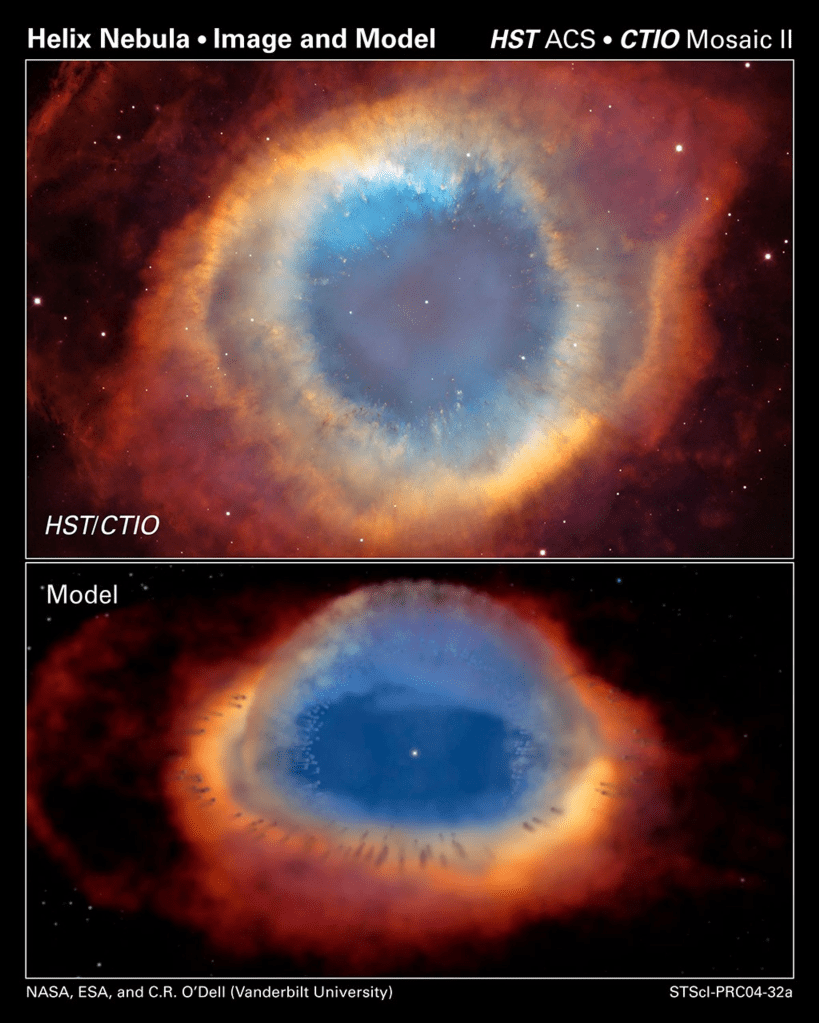

The Helix Nebula resembles a torus, but is actually two gaseous disks perpendicular to each other, which was determined from Hubble observations and careful velocity measurements. The inner disk is tilted relative to the outer ring, forming a barrel-like cylinder aligned towards the Earth, giving the illusion of a bubble. The outer disk brightens on one side due to compression against the interstellar medium as the nebula moves. Radial rays and filaments that extend outward are sculpted by stellar winds.

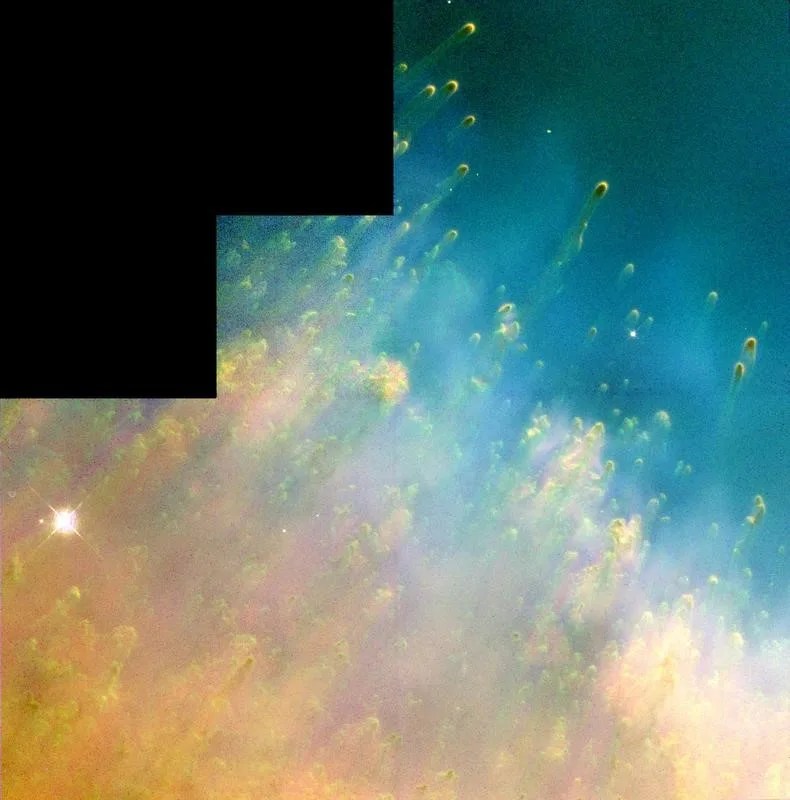

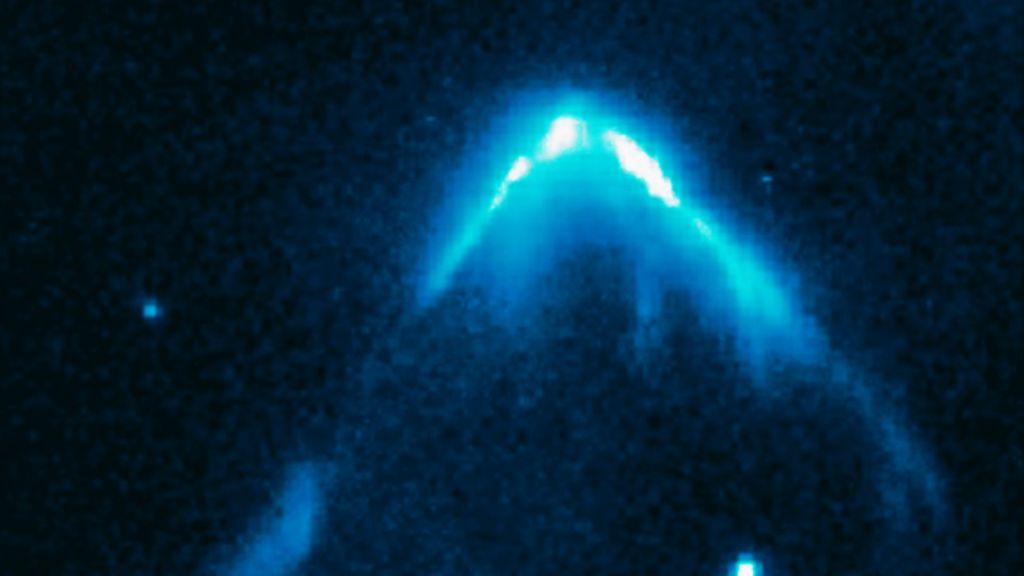

A prominent feature are thousands of knots that resemble comets along the inner rim, each with a dense head about twice the size of the Solar System, and tails stretching across 160 billion kilometres. These are formed when the fast, hot winds from the remnant white dwarf collide with slower, cooler gas that was ejected earlier, creating shock-excited structures that resemble spokes on a wheel. The knots are optically thick, shielding the molecular gas from ionisation, and may resemble a disk similar to a collar around the dead star. The tails are in the shadow of ionisation.

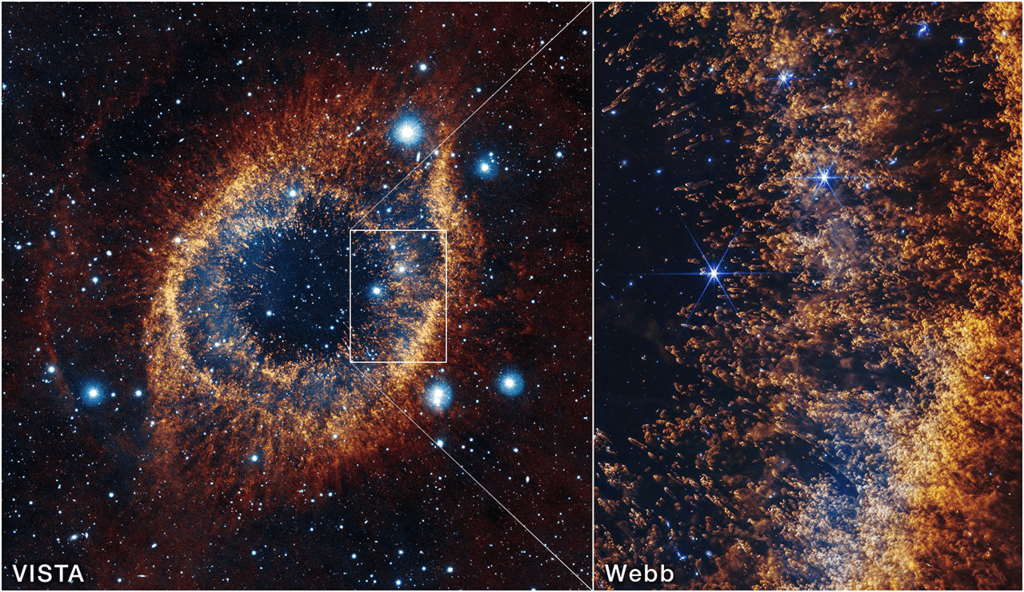

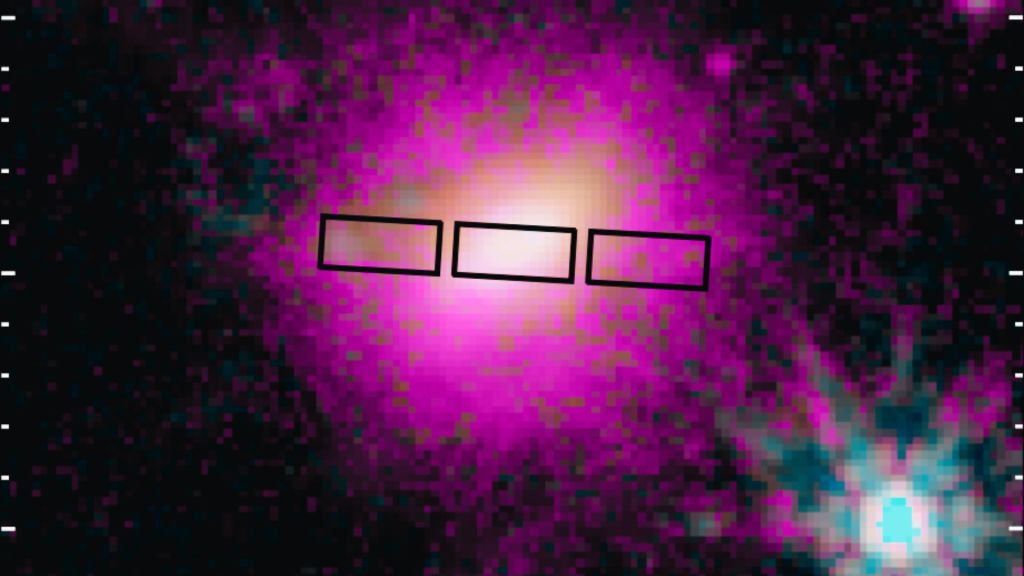

The distribution of the dust across the nebula is clumpy, and concentrated in the walls of the barrel. This dust is composed primarily of amorphous carbon. Observations by the European Herschel telescope has indicated the presence of water in the planetary nebula, with hydrogen gas forming a ‘firework’ pattern. The observations by Hubble reveal glowing oxygen in blue as well as hydrogen and nitrogen in red. Spitzer’s infrared observations revealed warm dust and complex molecules in the outer shells. Webb’s infrared observations revealed the comet-like pillars tracing gas shells, with the hot, ionised gas appearing blue, and hydrogen in yellow.

The Helix Nebula is window into the future of the Sun. In about five billion years, the Sun is expected to run out of nuclear fuel, balloon-up into a red giant star, and shed its outer layers, resulting in a planetary nebula. The shed material would be recycled into the interstellar medium for a new generation of stars and planets. The multiple ejections of the Helix Nebula hints at complex mass loss, with knots dissipating over time into faint striations. The Helix Nebula continues to be studied to refine models of nebular evolution.

Image Credits:

Infrared Views: ESO, VISTA, NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, J. Emerson (ESO); Acknowledgment: CASU

3D View: NASA GSFC

Cometary Knots 1: NASA, NOAO, ESA, the Hubble Helix Nebula Team, M. Meixner (STScI), and T.A. Rector (NRAO).

Cometary Knots 2: C. Robert O’Dell and Kerry P. Handron (Rice University), NASA

2.2-metre Max-Planck Society/ESO telescope: ESO

Spitzer: NASA, JPL-Caltech, Kate Su (Steward Obs, U. Arizona) et al.

Spitzer + Galex: Spitzer for the central nebula is rendered in green (wavelengths of 3.6 to 4.5 microns) and red (8 to 24 microns), with WISE data covering the outer areas in green (3.4 to 4.5 microns) and red (12 to 22 microns). Ultraviolet data from GALEX appears as blue (0.15 to 2.3 microns).Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Herschel Observations: Hubble image: NASA/ESA/C.R. O’Dell (Vanderbilt University), M. Meixner & P. McCullough (STScI); Herschel image: ESA/Herschel/SPIRE/MESS Consortium/M. Etxaluze et al.

Sources:

The creation of the Helix planetary nebula (NGC 7293) by multiple events

The nature of the cometary knots in the Helix planetary nebula (NGC 7293)

Herschel imaging of the dust in the Helix nebula (NGC 7293)⋆

Morphology and Composition of the Helix Nebula

Herschel spectral mapping of the Helix nebula (NGC 7293)

PS: This is an interesting paper on the fractal analysis of its structure. Could not find a way to include it into the main article! Fractal Analysis of the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293)

Leave a comment