An exoplanet is assigned a letter on its discovery, which is appended to the name of the star it orbits, starting with b, so we get Trappist-1 b, c, d, e, f, g and h. Here, all the terrestrial worlds in orbit around Trappist-1 were detected at the same time, so they were assigned letters according to the sizes of their orbits, with the smallest orbit getting assigned a letter first. Even this simple system ends up with confusing system architectures, as planets may not be discovered in the order in which they orbit their host stars. For example, we have 55 Cancri b, c, e, f and d.

The exoplanet naming convention is the extension of the Washington Multiplicity Catalog (WMC), a system adopted formally by the IAU in 2003 to tackle the problem of naming star systems with multiple stars. Stars in a multiple system are assigned capital letters such as A, B, C and so on. In hierarchical multiple star systems, lowercase letters are used for lower-mass companions, so the Aa, Ab and C. By this convention, the Alpha Centauri system should consist of Alpha Centauri Aa, Ab and C, but for historical reasons, these stars are known as Alpha Centauri A, B and Proxima Centauri. Astronomers have just discovered a giant exoplanet in orbit around Alpha Centauri A.

Circumbinary planets defy the convention

Now Tau Bootis b should actually be Tau Bootis A b, but the A is dropped in the names. When multiple stars in the same system host their own planets, the convention is followed and the letters are not dropped. When it comes to planets in orbit around two stars, or circumbinary planets, the convention fails utterly. When worlds were discovered in orbit around both stars in HW Virginis, they were provided numerical designations, HW Vir 3 and 4. The planets in the NN Serpentis systems are designated as NN Ser c and d. Both of these approaches simply denote the third and fourth objects in binary star systems. Astronomers have proposed fixing the convention through the judicious use of parenthesis.

Shown above are examples of how the exoplanets could be named by the proposed convention in systems of various architectures. The naming convention preserves information about the structure of the system that it belongs to. Star Wars and Star Trek both use a naming convention for exoplanets that use roman numerals, which is easy to understand. Dune appears to use such a system too, as we know from Ix.

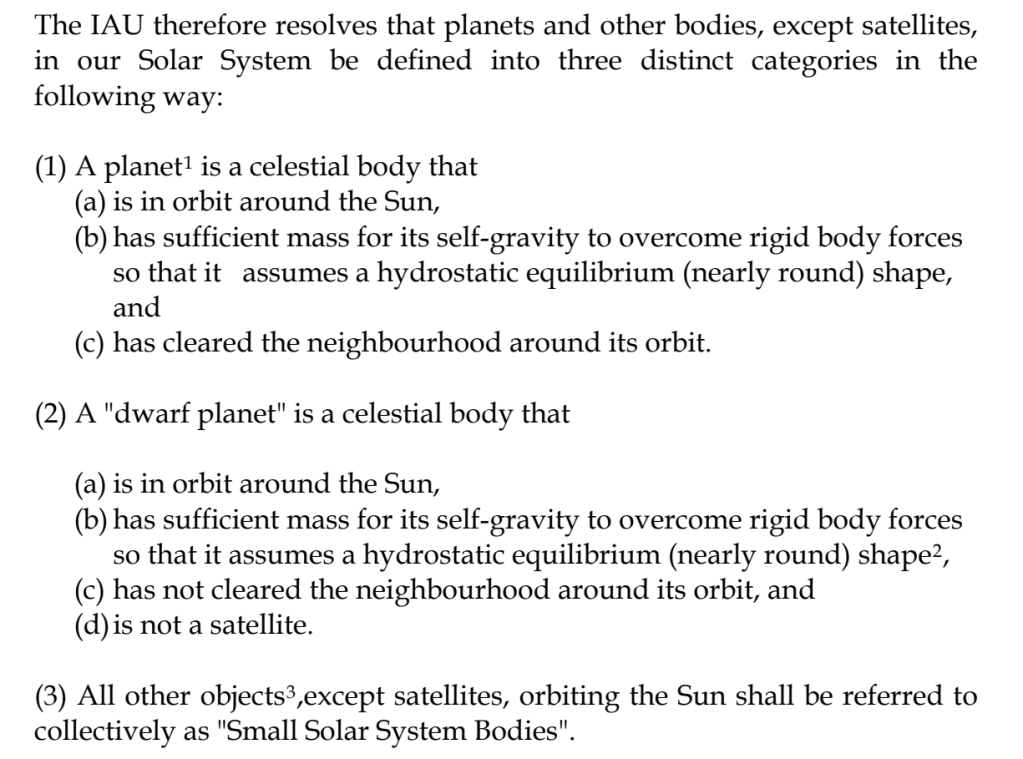

The official definition of a planet is deeply flawed

The IAU conventions are actually treated more like recommendations, with so many exceptions, because they might just not be the most official body with oversight on the exoplanet naming convention itself. This is because it is a union of astronomers, who primarily study stars. The researchers focused on studying exoplanets are planetary scientists. The definition of exoplanet itself is problematic as it gives a special status to the Solar System, implying that planets, dwarf planets and minor planets can only orbit the Sun, with other planetary systems made up of exoplanets, exomoons and exocomets. Forget exoplanets, the IAU cannot even formulate a common-sense, practical definition of a planet. The revised definition in 2006 has proven to be controversial, even if the reasons for excluding Pluto as a planet are accepted.

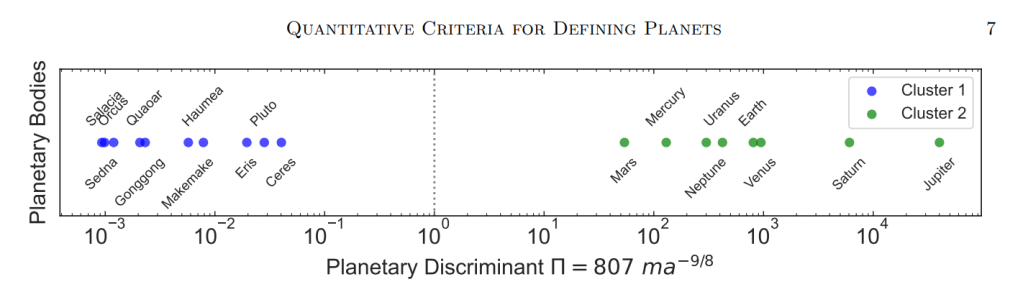

Now this definition of a planet depends on external factors that have nothing to do with the object being studied. Also, it excludes exoplanets for no good reason, it is just straight up factually wrong to say planets only orbit the Sun. The Sun has not cleared its orbit, and in fact frequently picks up quasi-moons, so the Earth is not a planet according to the IAU. The IAU definition for a planet is wrong, and this extends to the working definition for exoplanets as well. The definition for exoplanets referenced antiquity and the Copernican revolution that occurred half a millennium ago, also suggests the vague notion of having to clear a zone, and approaching hydrostatic equilibrium. The asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter is littered with objects that approach hydrostatic equilibrium to various degrees, including Vesta, Ceres and Pallas. The protoplanets and planetoids in circumstellar disks are not called exoprotoplanets or exoplanetoids as the exclusion is absolutely irrelevant in a scientific context to describe the nature of the object.

The current definition is based on the shape of the object, which is something that astronomers mostly cannot observe or study. We know that planets tend to be round, but we cannot directly see round things in orbits around distant stars, but we can estimate their masses. This is why a definition tied to the mass mades more sense for both planets and exoplanets. Planetary Scientists have called for an update on the definition of a planet, that includes exoplanets, and proposes a simple, three-step definition for planets. A planet is any object that:

- orbits one or more stars, brown dwarfs or stellar remnants and

- is more massive than 10^23 kg and

- is less massive than 13 Jupiter masses (2.5 X 10^28 kg).

Both planetary scientists and astronomers can benefit from a precise quantitative threshold, and the general public should be absolutely fine with scientists using a technical definition for planets. This may not be a common-sense definition, but it is definitely a practical one, that is not confusing. This definition is sufficiently broad in that it includes objects in orbits around stars, dead stars, substellar objects, with the upper mass limit capped at where objects grow large enough to begin deuterium fusion. Just calling exoplanets planets helps a lot to begin with, but even with the improved definition, the problems with exoplanet nomenclature are expected to persist. The definition of a planet and their naming convention both need to be updated to fix the system.

Leave a comment