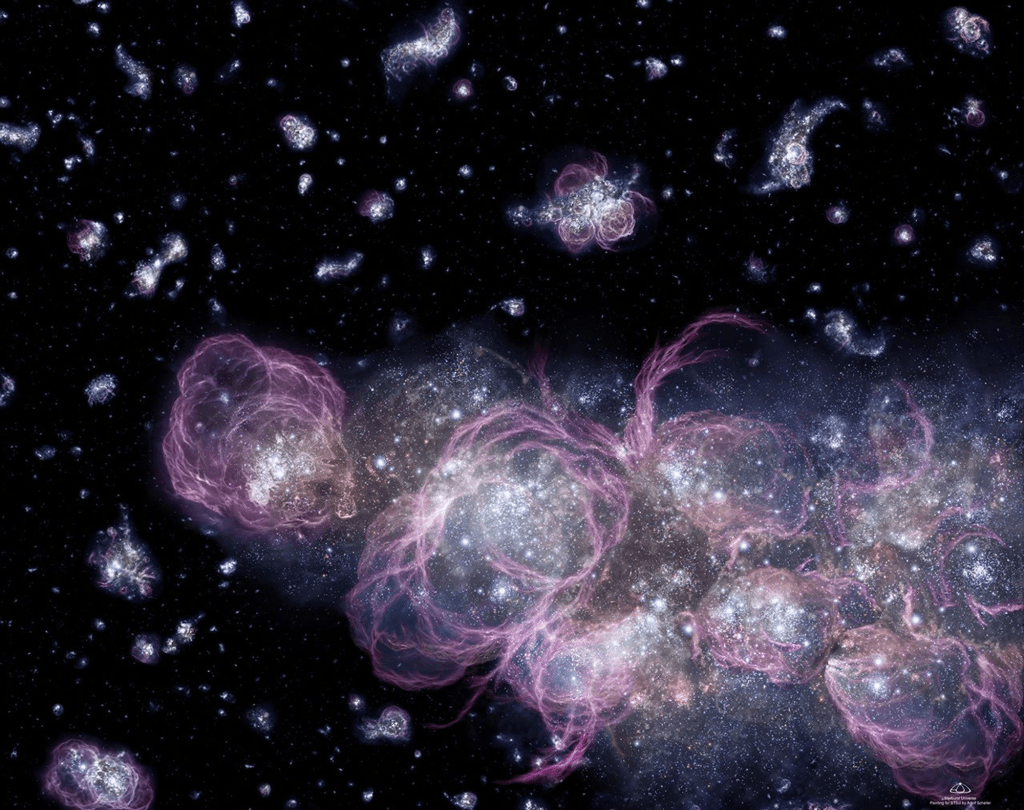

All the matter in the universe is just 0.0000001 per cent of the material created with by the Big Bang. The rest consisted of matter and antimatter in nearly equal measure, that annihilated each other in the moment of creation. A slight imbalance, a fundamental asymmetry known as Charge-Parity violation, resulted in a marginal fraction of matter surviving. Most of the matter that survived the destruction immediately following creation, was in the form of hydrogen, and a small amount of helium. The first stars were giants, collapsing in clusters within vast clouds of pristine, neutral hydrogen. These were massive stars the likes of which were never seen again, living short lives of a few million years, furiously fusing hydrogen into helium, burning out and exploding in violent supernovae, like strings of firecrackers.

Once these first stars ran out of hydrogen to fuel into helium, they fused a small amount of helium into heavier elements, moving upwards through the periodic table, forming lithium, beryllium, boron, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine and neon. When the stars exploded, they polluted or enriched the surrounding environment with heavier elements. A subsequent generation of stars were born from the debris of dust and gas, where the process repeated itself, with the stars fusing progressively heavier elements.

Diamonds in the Sky

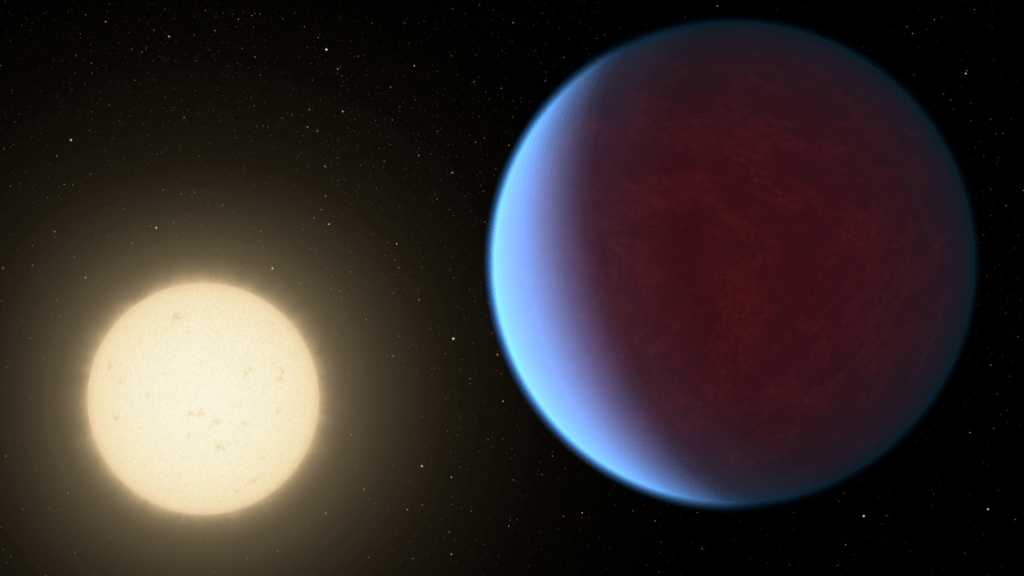

Dense knots in clouds of gas and dust collapse to form stars, with the infalling swirling matter flattening into circumstellar disks feeding embryonic stars. Once the protostar becomes hot and dense to sustain fusion, it can be called a star. Planets are assembled in the surrounding waste material. If the star is rich in carbon, the worlds in their orbits are also rich in carbon. Planets can have carbon-rich interiors. Scientists suspect that 55 Cancri e, in orbit around a k-type orange dwarf star at a distance of 41 lightyears from old Sol, in the constellation of The Crab, is suspected to be one such world.

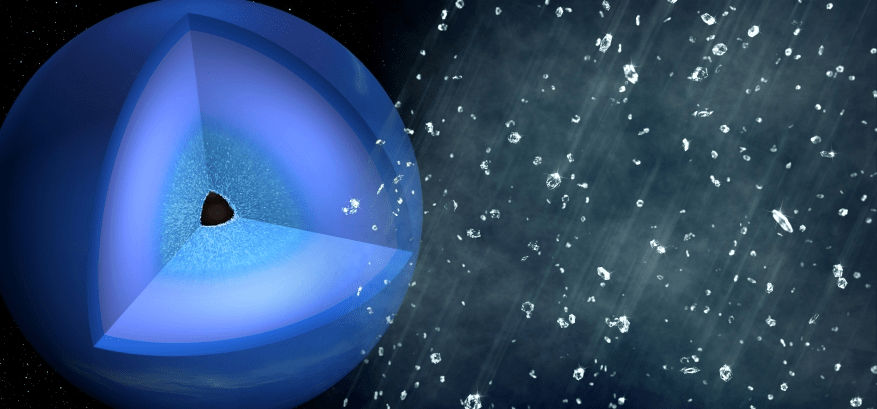

The debris disk surrounding a newborn star has a temperature gradient. Closer to the host star, the temperature causes volatile elements to evaporate. In the outer reaches though, water, ammonia and methane all exist as ices in vast quantities, that can clump together to form ice giants, similar to Uranus and Neptune in the Solar System. The pressures in the crushing interiors can reach 60 million times the atmospheric pressure of Earth at sea level. The temperatures can rise to 6700°C. Under the extreme temperatures and pressures, methane can pyrolyze or decompose into carbon and hydrogen. The shock compression of metallic carbon and graphite within nanoseconds can form diamond rain in the remote interiors of ice giants.

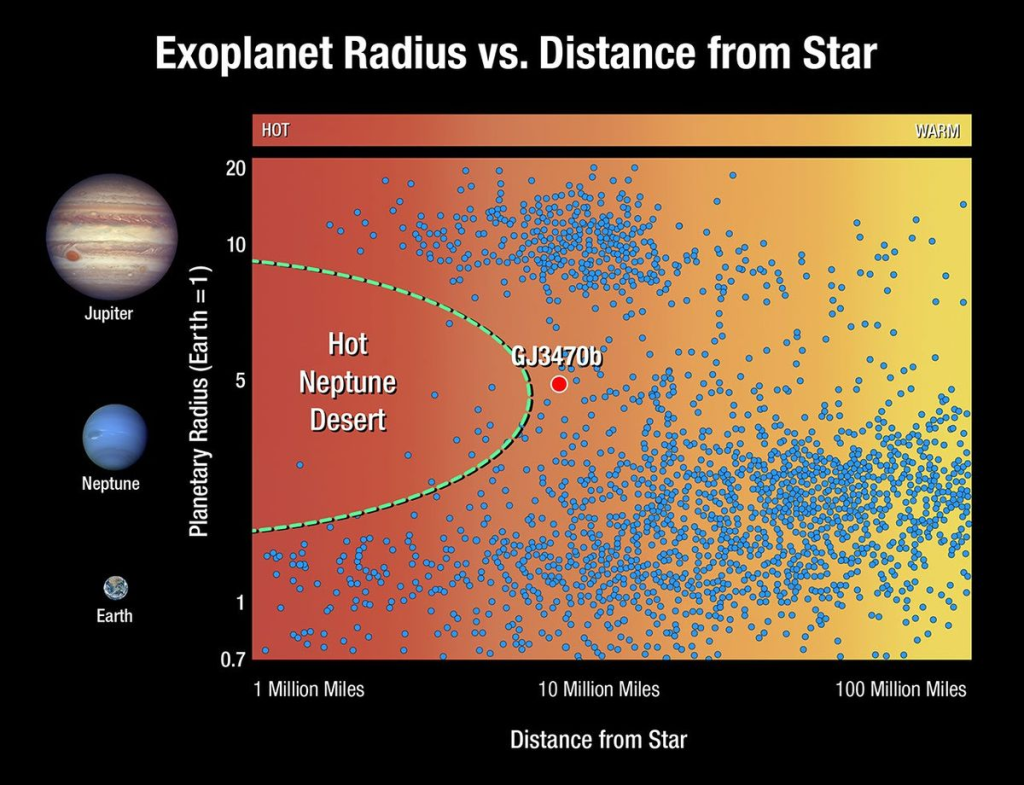

The cores of ice giants can be solid diamonds, of comparable size to terrestrial worlds. Now, planets that form in the outer reaches of star systems can migrate inwards, as evidenced by the discovery of over 500 ‘Hot Jupiter’ exoplanets. Some of these gas giants are being stripped of their outer atmospheres. Chthonian planets are hypothetical worlds whose gas envelopes have been stripped away entirely, leaving behind rocky or metallic cores. High-density exoplanets such as TOI-849 b could be the remnant cores of evaporated ice or gas giants. 55 Cancri e is not explicitly a stripped giant, but has a high-density and carbon-rich composition, similar to the core of an ice giant. The exoplanet contains about eight times the mass of the Earth, about a third of which is made up of graphite or diamond. In theory, distant stars may host a diamond planet in their orbits.

The Warm Neptune Desert

If these diamond planets exist, they are expected to be very rare. This is because of the Warm Neptune desert. Humans know of some 5,800 confirmed exoplanets, about 500 of which are Hot Jupiters. However, there is a scarcity of Neptune-sized exoplanets in tight orbits around host stars. Astronomers do not know for certain why this is the case, but ice giants seem to be less common than expected in close proximity to their stars. One possible explanation is that the outer layers of all these worlds might be stripped away by the stellar radiation, leaving behind a dense core.

TOI-849 b, at a distance of 741 lightyears in the constellation of Fornax, may just be one such stripped core of an ice giant. GJ 436 b is an ice giant in the Warm Neptune desert whose atmosphere is being stripped away by the action of its host star. This exoplanet is at a distance of 31.9 lightyears in the constellation of Leo. There may be many diamond worlds scattered through the vastness of space, ghosts of gas giants, relics of planetary migration and photoevaporation. These drifting, evolved remnants of planetary alchemy are forged by pressure, transfigured by heat and scarified by stellar winds. These natural jewels can remain for billions of years, long after the stars fade.

Image Credits:

First stars: Adolf Schaller for STScI

Diamond Rain: LNLL

55 Cancri e: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Sources:

The ice layer in Uranus and Neptune—diamonds in the sky?

A Possible Carbon-rich Interior in Super-Earth 55 Cancri e

Dearth of short-period Neptunian exoplanets: A desert in period-mass and period-radius planes

Repulsive forces of simple molecules and mixtures at high density and temperature

Unusual chemistry of the C–H–N–O system under pressure and implications for giant planets

Leave a comment