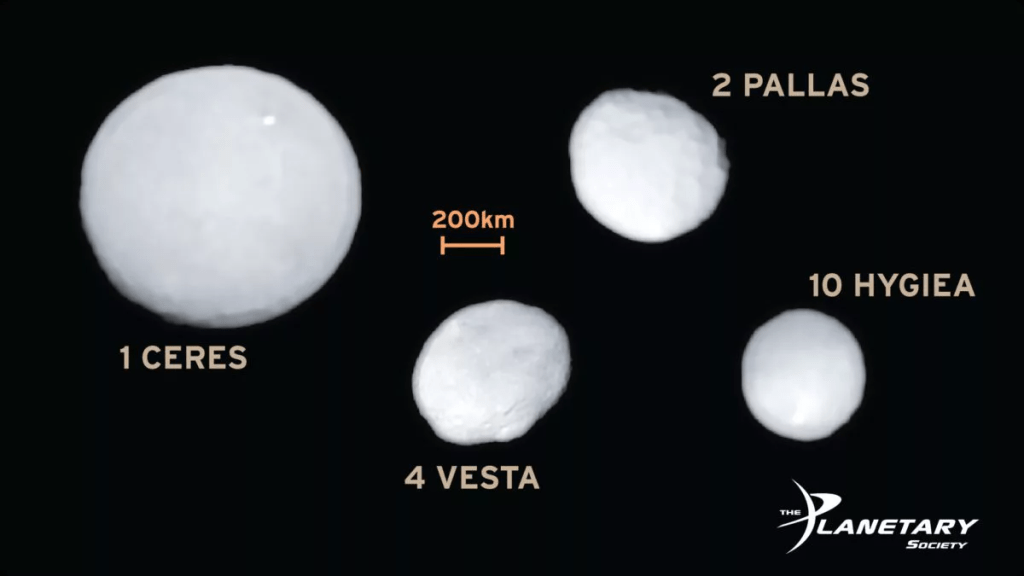

A debris field with pebbles, boulders, rubble piles and larger planetesimals with differentiated interiors occupies a 200 km wide belt between the orbits of Mercury and Jupiter. Most of the lumpy asteroids are shaped like tops, with a characteristic bulge formed because of their spins. Between diameters of 200 and 400 metres wide, the asteroids start become spherical under the influence of gravity. Ceres, the largest asteroid at 940 km wide is nearly spherical, while the 525 km wide Vesta and the 513 km wide Pallas are oblate and irregular.

Most of the objects in the Asteroid belt are a mixture of material leftover from the birth of the Sun. The gravitational influence of Jupiter prevented the formation of a world in the asteroid belt. Some of the asteroids though, are results of a far more complex process, they are the fragments of protoplanets that were battered to bits in the chaotic infancy of the Solar System. These are the asteroids that are fragments of differentiated planetesimals, worlds with a crust, mantle and core. The metallic asteroids are believed to be the cores or fragments of cores of long-lost worlds.

The Graveyard of Ambition

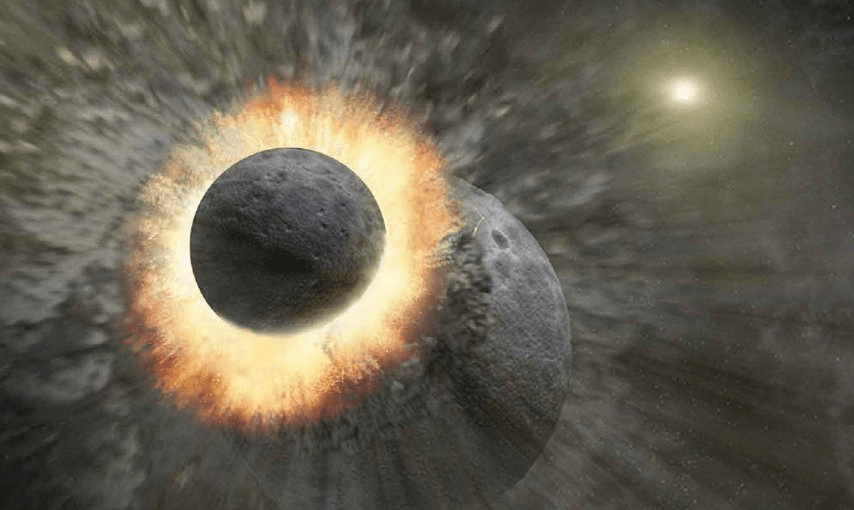

The planets were assembled in the disc of gas, dust and ice falling inwards into the Sun. The spin of the material had flattened it along the ecliptic plane. Within the first million years after the Sun began sustainably fusing hydrogen into helium, the the material in the circumstellar disk started coalescing into pebbles, boulders and mountains. As these clumps grew beyond 400 metres in size, they started trapping heat. The heat from radioactive elements melted rock and metal within the dense interiors of these worlds. Under the influence of gravity, the metals sank towards the cores, while lighter silicates floated into the mantle. The lightest melts hardened into crusts, the skins of protoplanets.

Around a newborn Sun, the temperatures were hot enough for planetesimals between 50 and 100 km to have differentiated interiors before the radioactive elements decayed. The collisions themselves could easily melt rock, with a pair of colliding 50 km wide rocks at 10 km per second generating enough heat to rival the surface of a small stars, resulting in a bubble of molten rock. Gas drag in the early nebula surrounding a newborn Sun could funnel metre-sized rocks into growing planetesimals through a process called pebble accretion, stoking furnaces deep in the interior of a planet. A 200 km wide body forming over 100,000 years would hit 1500°C, with liquid oceans of metals and silicates arranging themselves in layers.

Water added a twist to the process, with some asteroids indicating the presence of hydrated minerals, including clays that can only be formed on parent bodies with water. Asteroid Bennu has traces of being a fragment of a watery planetesimal. Melted by the heat, water would have circulated through mantles, altering rocks. A protoplanet 300 km wide could have hosted a subsurface ocean, with a frozen shell and hydrothermal vents in the interior. The bigger ones measuring over 500 km across may also have hosted magma oceans. These protoworlds were constantly colliding. Some asteroids are intact survivors with layered interiors, while others are fragments of differentiated protoplanets.

Violent Dawn

The biggest asteroids in the belt stand out as survivors of the demolition derby. The interiors bear the marks of differentiation. Vesta, 525 km across has a surface of patchwork and craters and dark streaks. It gleams brightly and has a iron-nickel core about 110 kilometers wide, nestled in a mantle of silicate rock, topped by a dusty crust of basaltic rock. Such igneous rocks are formed only by molten rock from the interior being squeezed out onto the surface. Survivors such as Vesta make up less than 10 percent of the mass in the asteroid belt. Some of the larger asteroids bear faint magnetic signatures in their rocks, indicating the presence of spinning metal cores in the distant past, generating a dynamo effect.

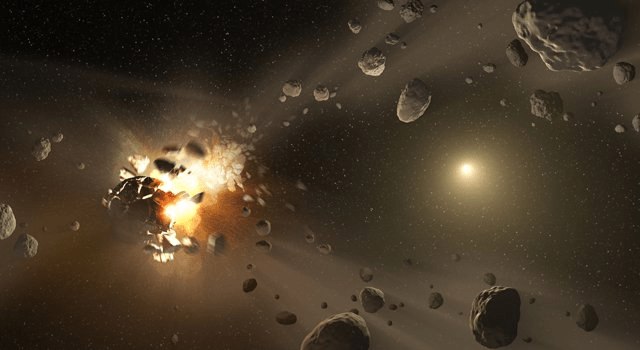

An impactor measuring 50 km wide was sufficient to cause a cataclysmic destruction of protoplanets between 200 and 300 km wide. The impact releases as much energy as a billion atom bombs, causing fragments of the world seed to scatter. The smaller 50 km wide asteroids were far more common than the 200 to 300 km wide protoplanets. The asteroid Adeona is potentially a 151 km wide chunk of the mantle of a protoplanet. Psyche, a 226 km wide asteroid is dominant in metal, with some mantle remnants clinging to a stripped planetary core. The 100 km wide Lutetia or the 25 km wide Gabriella are both dominated by metals. Lutetia is believed to be a fragment of a protoplanet with core exposure, while Gabriella is the sliver of the pure metallic core of a protoplanet that was between 100 and 200 km wide before it got battered to bits. Theories indicate that the asteroid belt once harboured dozens of protoplanets, their combined mass reaching between 10 and 20 times the mass of the Moon, now reduced to four per cent by collisions and ejections.

It took the earliest forms of unicellular life 200 million years to spring up on Earth. Life could have potentially emerged on a protoplanet that formed before the Earth. A planetesimal 500 km wide with a subsurface ocean between 20 and 100 km deep and a saltwater ocean under pressure maintained at temperate conditions between 0 and 40°C might have hosted microbial chemistry. Even a ball of mama rich in metals could drive prebiotic reactions in cracks. When these worlds were battered to bits, some would have reached Earth as meteorites. These fragments loaded with organics could deliver amino acids or nucleobases between 4.1 and 3.8 billion years ago, a period known as the Late Heavy Bombardment. This episode may have played a role in the emergence of life on Earth.

Image Credits:

Largest Asteroids: ESO/P. Vernazza et al./MISTRAL algorithm (ONERA/CNRS)

Creation of asteroid families: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Moon forming event: NASA/JPL-CalTech/T. Pyle.

Comets in a young Solar System: NASA/JPL

Early Solar System Collision: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Psyche: NASA

Leave a comment