About 4.6 billion years ago, the Sun collapsed within a swirling nebula of gas and dust, becoming hot and dense enough to sustain cooking hydrogen into helium. The Sun, a glowing ball of plasma, was surrounded by a chaotic nursery of gas, dust and ice, a swirling disk where the planets were assembled. Grains of dust and ice formed clumps, drawing in more material and growing to pebbles, then boulders, and eventually mountains. Once these conglomerations grew to between 400 and 600 kilometres wide, they start becoming spherical, the seeds of worlds.

Some of the planetesimals grew large enough to melt and differentiate into layered structures, with the heaver metals sinking to the core, a mantle of molten rock, and at times, even a solid crust. These protoplanets were the scaffolding around which worlds were constructed, but things can go chaotically wrong during the process of architecting the cosmos. Instead of coalescing into a single planet straddling the gap between the tiny rocky Mars and the Gas Giant Jupiter, a world met a violent end, battered into fragments by cataclysmic collisions, reducing a planet that could have been into rubble. Today we call these fragments asteroids, and their story is one of cosmic tragedy, resilience and revelation.

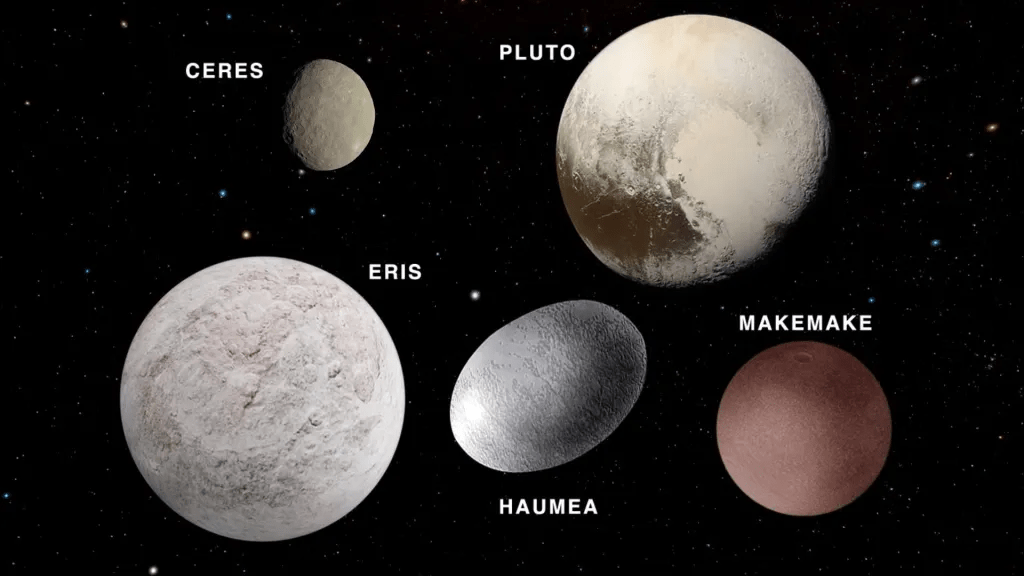

Many planetesimals were formed around a newborn Sun, and quite a few of them occupy the main belt between Mars and Jupiter, including Vesta, Ceres, Pallas and Hygiea. Large icy bodies in the outer solar system, including Pluto, Eris, Haumea and Makemake are all protoplanets, not just dwarf planets. The Plutonian moon Charon, the Neptunian moon Triton and the Uranian Moons Titania and Oberon all may be protoplanets that formed independently and subsequently captured. The Moon of the Earth was formed by material ejected by a protoplanet roughly the size of Mars crashing into Earth about 4.4 billion years ago. This object, called Theia is embedded deep within the Earth, so the Moon actually has two Earths.

In 1801, the Italian Mathematician Giuseppe Piazzi discovered Ceres while carefully mapping the sky. Initially, he believed it to be a star, but then found out on subsequent observations that it was moving along a steady trajectory. He considered the possibility that it was a comet, but it lacked a nebulosity. He suspected Ceres could be a comet but was conservative about claiming such a discovery. Over the next few decades, astronomers discovered a number of small planets, or minor planets, including Pallas, Juno and Vesta. Minor planets remains the technical term for asteroids, and acknowledges their diminutive sizes compared to the giants that occupy the outer Solar System. There remains a deeper implication to the term, a double meaning that prevents it from being a misnomer, the asteroid belt could be a graveyard of a planet that never was, or worse, one that was formed and was subsequently torn apart.

Finding a belt of space rocks between two worlds captivated early astronomers, who theorised that a planet should have orbited the Sun in the region. The formation of such a world may have been thwarted by a gravitational tug-of-war between the Sun and the might Jupiter. Others imagined a more dramatic fate, of a fully formed planet that was shattered by a cosmic catastrophe. Now we understand that these asteroids are the battered remains of a far more dynamic process. Geophysical analysis, meteorite studies and spectroscopy all indicate that asteroids are the bones of much larger bodies, planetesimals and differentiated bodies, that once swarmed around Baby Sol.

The spinning disk of debris surrounding a newborn Sun was a brutal place, a cosmic demolition derby where collisions were the norm. The differentiated parent bodies smashed into one another over millions of years, in a process now termed the ‘battered to bits’ scenario. The result was a swarm of fragments ranging in size from pebbles to mountains. We know this because the surfaces of asteroids contain basaltic fragments, formed from the molten rock flowing out of volcanoes onto terrestrial surfaces. Such igneous rocks form only in differentiated worlds with a crust and mantle. The liquid interior of worlds need to escape onto a solid exterior, like a popped pimple, for such rocks to form. The chemical signature of a basaltic crust on some asteroids support the idea that they are shards of a shattered protoplanet.

Iron meteorites are believed to be remnants of the metallic cores of differentiated planetesimals, their nickel-iron composition is similar to the core of the Earth. The intense heat and pressure conditions needed to form these metallic space rocks can only occur in the hearts of worlds. Other meteorites reveal the chemistries of mantles and crusts, displaying a wide range of compositions that mirror the layered interiors of planets. The diversity of the meteorites and asteroids reveals a history of creation and destruction. Each fragment of rock is a time capsule that tells an incredibly ancient and complex story. The early Solar System was brimming with potential and peril.

Not all asteroids are fragments of shattered worlds. Some like Ceres, may be survivors, original condensations from the Solar Nebula that increased in size but never reached planethood. These are relics from the infancy of the Solar System. The surface of Ceres is pockmarked by craters, with possible signs of subsurface ice, indicating a complex history. While Ceres has survived, it has not escaped the chaos of the asteroid belt, and bears the scars of collisions. Some of its neighbours may have chipped off the surface.

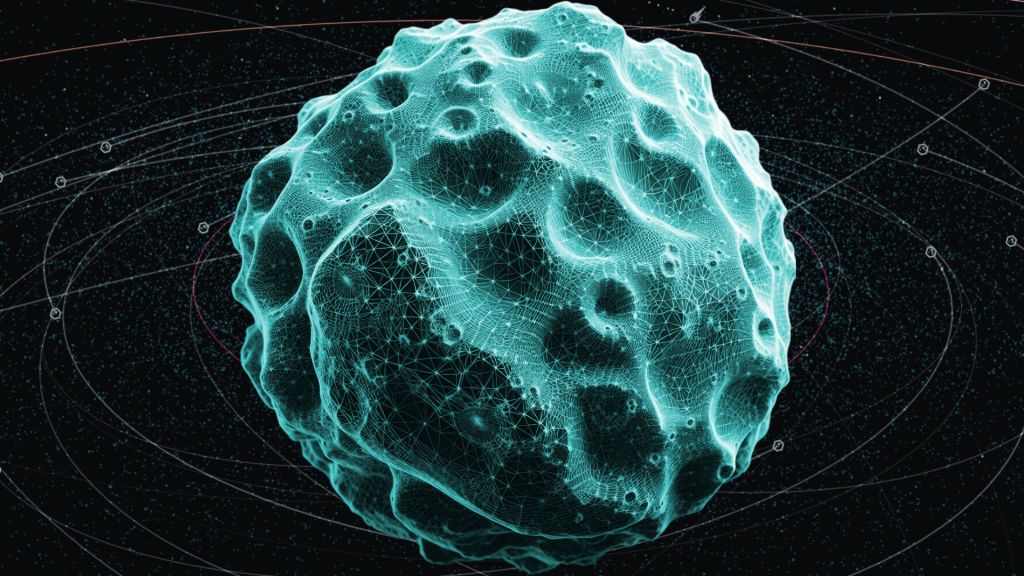

There are populations of asteroids distributed throughout the Solar System, including in the same neighbourhood around the Sun as Earth. These Near Earth Asteroids may be scattered planetesimals, ejected from their original orbits because of nudges from the Giant Planets in the outer Solar System.

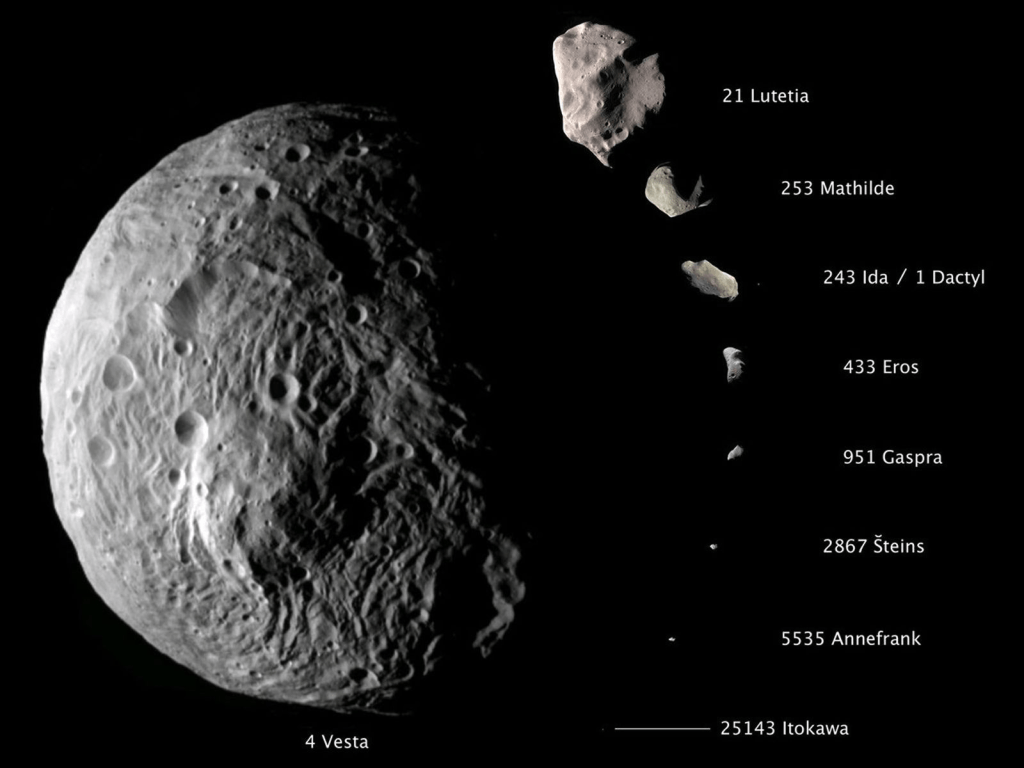

In the 19th century, when Ceres and its ilk were first classified, any body orbiting the Sun could have been considered a planet. The term has evolved since then, and today the official definition has become problematic and controversial as it does not really draw a sharp line focusing on geophysical characteristics such as size, shape and internal structure. Instead, planets have to be large enough to become spherical under the influence of hydrostatic equilibrium, and to have cleared their orbits, which is an external criteria that has nothing to do with the object. While scientists debate endlessly over a practical, simple and straightforward definition of a planet, it is sufficient to just call them large, round worlds, in the interest of common sense. Asteroids, by contrast are tiny, irregularly shaped, and often the products of fragmentation

So, are asteroids the remnants of planets? Not exactly—at least, not in the way we define planets today. The term “planet” has evolved since the 19th century, when Ceres and its ilk were first classified. Back then, any body orbiting the Sun might have been called a planet. But modern science draws a sharper line, focusing on geophysical characteristics like size, shape, and internal structure. Planets are massive enough to become spherical and clear their orbits of debris; asteroids, by contrast, are smaller, irregularly shaped, and often the products of fragmentation.

Asteroids, the pristine fragments from the infancy of the Solar System, with their jagged edges and battered surfaces, are a haunting reminder of countless failed planets, and that the universe has boundless potential for unrelenting destruction. The collisions that shattered planetesimals are the same ones that built planets, and further, made then habitable, delivering the material for oceans and atmospheres, and the complex organic molecules necessary for the business of life.

Image Credits:

Vesta Sizes Up: NASA/JPL

Dwarf Planets: NASA

Planetesimal Collison Around Star HD 166191 (Illustration): NASA/JPL-Caltech

NEOs: ESA NEO Toolkit

IC 418: Hubble

Moons of Jupiter: NASA

Probe: Bing Image Creator

Leave a comment