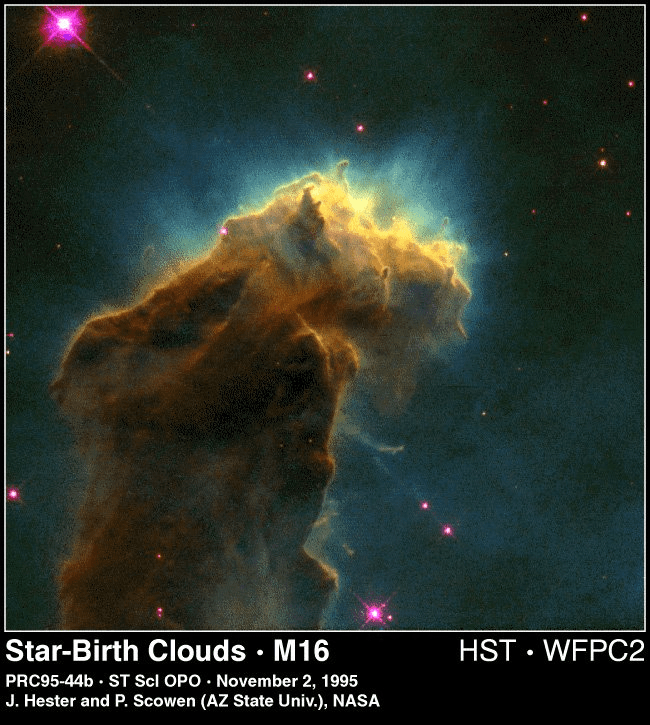

Most visible matter in the universe is made up of hydrogen mist, stored in clouds of vapour and occasional grains. The dust of dead stars are the raw material from which new stars are born. In the vast emptiness of space, the temperature drops, gas becomes more comfortable with density, and gravity starts its work, causing particles to swirl inwards. The mist of hydrogen gas may be disturbed by passing shockwaves from supernovae, or the jets from newborn stars, forming clouds with dense knots. The mass densities begin to grow, accreting more of the surrounding material.

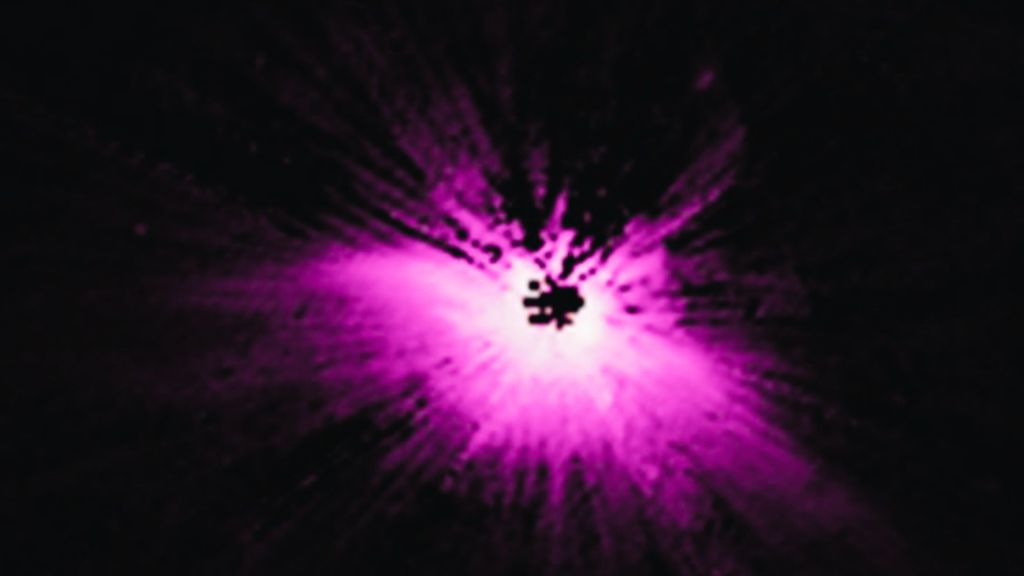

As the gas, dust and ice start falling inwards, the temperature and density of the protostar increases. The heat of compression causes a pale, dim glow. The matter spiraling inwards collapses into a disc because of the spin. Tendrils of magnetism from the star-seed propel matter into protostellar jets. These jets are essential for shedding angular momentum from the collapsing molecular cloud, allowing for a star to be born, and planets to be assembled in the leftover material.

A protostar releases energy in sputters because of temporary bursts of heavy hydrogen or deuterium fusion and gravitational collapse. The core of the star eventually becomes hot enough and dense enough to fuse hydrogen into helium. The star will do this continuously, till it runs out of hydrogen to fuse. The newborn star rapidly blows away any leftover gas and dust, as its birth cry. Radiation pressure from the nuclear furnace at the core of the star pushes the ball of hot gas to expand, even while the gravitational influence of the crushing mass density pulls the star towards a collapse. Eventually, the star settles down into an equilibrium, and can shine steadily for billions of years provided it is small enough.

The newborn star stirs up a cauldron of alchemy within the circumstellar disk, with ices, dusts and gases mixing and interacting at different temperatures. Methane, ammonia and water form seeds of further complexity, with ices occupying the frigid outer regions, and the heat in the inner regions driving volatility, forging amino acids and sugars. Carbon, oxygen and nitrogen all interact and bind, in a dance of elements.

In a warm envelope of gas around the host star, methanol, formaldehyde and more complex organic molecules are formed, and they drift outwards, carried by the solar wind. This is a corino, a forge of prebiotic chemistry, that seeds the circumstellar environment with the promise of life. Beyond the corino, the leftover material begins to collapse into pebbles, then boulders then planetesimals, the bones of worlds. The inner regions allows for the formation of rocky planets, rich in metals. The outer solar system is for the gas and ice giants, which also have more material available for accretion in their orbits. The winds from the newborn star clears the system of chaff.

Where there is water, there is life. Liquid water can only exist on temperate worlds, with just the right temperature and pressure conditions. The subsurface oceans and lakes embedded within the crusts of ice moons are also suitable habitats for lifeforms. Geothermal vents are a great place to look, as are warm little ponds. The principle may extend to a wider range of liquids that can act as solvents in exotic biochemistries, including liquid hydrocarbons on colder ice moons.

Recounted for any who roam the endless night.

Leave a comment