This is an indulgence, an admittedly crazy peek inside a rabbit hole. The theory is that all galaxies are teeming with life, and that the cosmic ancestry of all living things across spacetime can be traced back to a young universe with habitable conditions. These first life forms, born not within any single planet but across thousands of worlds, seeded the cosmos with biological debris, or even dormant spores, allowing life to spring up readily in any favourable environment. There is no way to balance out this topic, any discussion on it has to be inherently biased. Science is not free of politics, and the spats at times, can get incredibly dirty. Scientists can also gang up against each other, and prosecute, contain or simply ignore ideas. If a claim requires a revision of deeply held ideas, then the evidence has to be stronger. Laplace’s principle of ‘the weight of evidence for an extraordinary claim must be proportioned to its strangeness’ was simplified into an aphorism made popular by Carl Sagan, ‘Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence’.

Widespread acceptance of novel ideas and so-called paradigm shifts are rarely sudden. Humans will have to slowly creep towards the idea that life on Earth may not be such a unique phenomenon. This slow journey will have to be supported by a progression of studies, and a series of increasingly targeted missions with specific payloads are necessary for confirming something as trivial as global subsurface oceans on the ice moons orbiting the gas giants, or that there is water on the Moon, or that Mars was once wet and may still be so today. Mainstream science marches slowly and surely, even if we know the gradual progress is towards the same eventual conclusion.

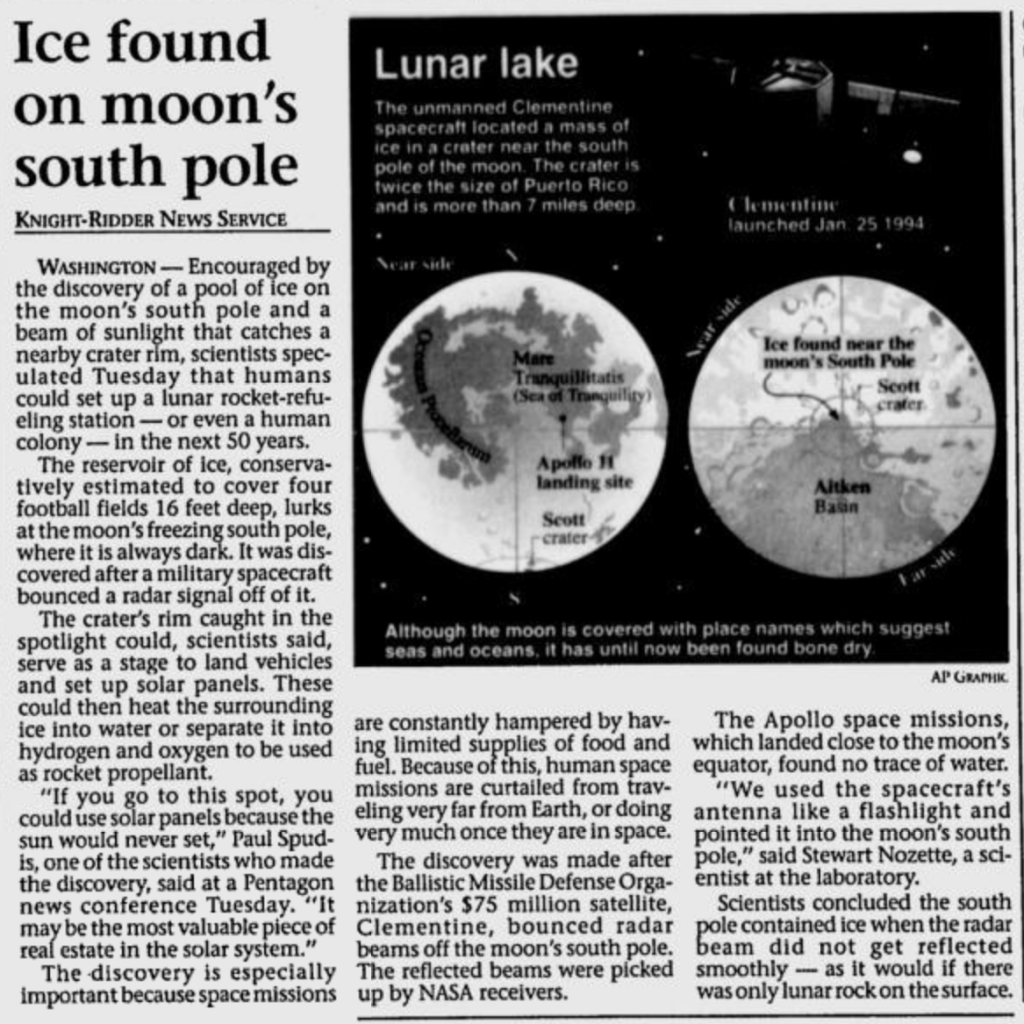

The conditions necessary for water to exist in the lunar south pole had been figured out in 1952 itself. The Clementine Spacecraft discovered these conditions, leading to this announcement in the Lawrence Journal-World on 4 Dec, 1996. A probe has yet to confirm the presence of water within a PSR with in-situ observations.

Evidence is still mounting towards these inevitable conclusions mentioned. It can take decades for evidence to catch up with theories. If scientists are so strict with themselves when it comes to what is widely accepted, then imagine how sceptical they must be for ideas that are not. This can put an unnecessarily harsh burden on those proposing radical ideas. Now, both sides of an issue can feel prosecuted, a good example being the hypothesis advanced by Luis and Walter Alvarez on an asteroid impact wiping out the dinosaurs, the idea was criticized before being accepted, a process that drowned out a competing theory that the extinction was caused by excessive volcanism. Dewey McLean has documented the resulting feud, and was also prosecuted for supporting a competing hypothesis. Scientists have still not resolved the issue, with new papers constantly supporting one of the two sides, and some researchers suggesting a combo, with the volcanism causing most of the extinction, and the asteroid providing the finisher.

Both sides on the Pluto Controversy are prosecuted as well, which is not that surprising considering both sides fail to provide practical solutions that benefit everyone. Let us just call these two camps astronomers and planetary scientists for the sake of simplicity. The planetary scientists want to define planets by their internal characteristics, and consider any spherical body smaller than stars as planets, including all the round Moons and Dwarf Planets in the solar system. There would be around 110 planets in the solar system then. The astronomers, well they really cannot come up with a good definition for a planet, and all we really need is a utilitarian, common sense definition, leave Pluto out, call it a Dwarf Planet, impose arbitrary mass and diameter constraints, all that is fine, but just come up with a definition that does not require something as obtuse as clearing the ‘neighbourhood around its orbit’. According to the official definition of the planet, the Earth is not one! A practical problem here is that the worlds in orbits around other stars are not planets, only those that orbit the Sun. Scientists have yet to reach a consensus on what a planet even is. This is yet another ongoing controversy in science.

Point is, scientists on differing sides of a controversy are prosecuted and ridiculed, but that is only half of the problem. There is a deeper problem to address in this particular controversy. The problem is partially about how life emerged, but also about how extraordinary life is. The answer to the latter depends on the answer of the former. The evidence necessary to prove life is spread across the universe may not need to be so extraordinary after all, if the hypothesis is true. This is just a shift in perspective about what life is, and not a big logical leap to make. To be clear the contention here is not that life manages to spring up in favourable conditions, repeatedly, but that the whole cosmos is a biosphere. How strange the idea is, and how strong the evidence needs to be to support it, is up for you to decide. It is worth considering here that the theory of panspermia, where all life in the cosmos has a shared origin, challenges the notion of biochemistry emerging on a range of exotic worlds, including those with hydrocarbon lakes on the surface, and water worlds with hydrogen-rich atmospheres, which would also make life common across the universe. Hopefully, this lengthy disclaimer is enough of a guardrail. The arguments presented henceforth might be compelling, but do not be easily convinced. Be a sceptic. Sit back, hold tight, and enjoy the ride while we bash scientists, just to explore a contentious hypothesis.

Dark Arts

Science thrives on scepticism. It is a discipline designed to question, refine, and overturn ideas when compelling evidence emerges. Yet, when certain theories challenge established paradigms too fundamentally, they face resistance not just from data-driven scepticism, but from entrenched cultural and institutional biases. The history of science is punctuated with stories of ridicule and rejection before eventual vindication. From heliocentrism to continental drift, many transformative ideas have initially been dismissed as heretical or absurd. Among them, the idea that life did not originate on Earth, but was instead seeded from the vast reaches of space, has faced particularly unyielding opposition.

Here, we examine the hurdles faced by scientists advancing the theory of cosmic panspermia—the notion that life’s origins are extraterrestrial. It is a story of censorship, suppression, and the slow, unrelenting march of evidence toward an idea once deemed unthinkable.

The Warm Little Pond

The prevailing view of life’s beginnings—the ‘warm little pond’ hypothesis—traces back to Charles Darwin and remains deeply ingrained in scientific discourse. This Earth-centric theory posits that life arose from a primordial soup, given the right combination of organic molecules and favourable conditions. However, the theory of panspermia, first hinted at by Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius in the early 20th century, suggests that microbial life could have originated in space and been transported to Earth via comets, meteoroids, or interstellar dust.

Illustration of a primordial Earth: Peter Sawyer / Smithsonian Institution.

Despite its compelling logic, panspermia disrupts conventional assumptions about life’s origins. If true, it implies that the seeds of biology may predate our planet, forcing us to reconsider not only where but how life emerges in the cosmos. This notion, which should invite curiosity, has instead provoked resistance.

Gatekeepers

In the early days, proponents of panspermia had a voice in respected journals, and researchers investigating cosmic biology found open avenues for publication. But this changed dramatically in the 1980s. As evidence mounted—ranging from the detection of organic molecules in interstellar space to the discovery of complex organics in comets—the gatekeepers of science hardened their stance.

Between 1982 and the present, a striking trend emerged: research supporting panspermia began facing systematic obstacles in publication. Work that once found a home in mainstream journals was either summarily rejected or subjected to disproportionately harsh scrutiny. By unspoken consensus, the topic was deemed taboo. Funding for research on extraterrestrial life’s role in our biological heritage dwindled. Scientists who pursued the idea risked professional marginalization.

Scientific journals and institutions act as arbiters of credibility. Peer review, at its best, ensures rigor and reliability. But it can also serve as a mechanism for preserving orthodoxy, filtering out research that challenges foundational assumptions. The gatekeeping of panspermia illustrates this dilemma.

The resistance was not merely passive neglect but active suppression. Reports of fossil-like structures in meteorites published in Nature by Claus and Nagy—were swiftly countered with high-profile refutations also in Nature. The message was clear: deviations from the accepted model of abiogenesis on Earth would not be entertained. As evidence for organic-rich comets and interstellar biomolecules accumulated, attitudes should have softened. Instead, the wall of resistance grew stronger, solidifying an implicit doctrine that confined the origins of life to Earth alone.

Microfossil Shootout

Perhaps the most striking example of this resistance is the case of microfossils in meteorites. The discovery of potential microbial fossils in carbonaceous meteorites should have been groundbreaking—a paradigm-shifting moment in astrobiology. Instead, it was met with immediate dismissal. Critics argued contamination, misinterpretation, and flawed methodology, often before alternative analyses were even considered. The reaction was not one of open inquiry but of categorical denial, indicative of an ideological rather than empirical rejection.

Despite these obstacles, nature itself provides a steady accumulation of clues pointing toward an extraterrestrial origin of life. Organic molecules permeate space. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons—complex organic compounds—are found throughout the universe. In Earth’s biosphere, nearly all organic material is biogenic in origin. Why, then, should we assume that similar compounds in space are purely abiotic? The convergence of evidence suggests a continuity between the chemistry of life on Earth and that of the wider cosmos.

Life in Intergalactic Tunnels

The probability of life emerging in a strictly terrestrial setting is constrained by time, environment, and biochemical complexity. A cosmological setting for life’s origins, in contrast, allows for a far richer and more plausible narrative. The vastness of the universe, spanning billions of years and countless planetary systems, provides the necessary conditions for life to emerge, evolve, and spread. Recent discussions by researchers such as Gibson and Schild reinforce this perspective, arguing that the origin of life must be considered within an astrophysical framework rather than a purely geochemical one.

Resistance to unconventional ideas is not unique to panspermia, but the intensity with which it has been opposed is revealing. The reluctance to consider an extraterrestrial origin of life is not purely scientific; it is cultural. Accepting panspermia forces us to abandon the notion of Earth as a singular, privileged incubator of biology. It suggests that life is not an anomaly but an expected consequence of cosmic processes. Such an idea disrupts long-held perspectives and requires a willingness to rewrite textbooks.

But science is not static. Just as continental drift was once derided before becoming fundamental to geology, so too might panspermia transition from heresy to accepted fact. The question is not whether the evidence will continue accumulating—it will. The question is whether we are prepared to follow where it leads.

Progress in science is often stymied not by a lack of evidence but by an unwillingness to question deeply held beliefs. The history of panspermia is one of missed opportunities and institutional resistance. But it is also a testament to the resilience of an idea that refuses to fade, bolstered by every new discovery that hints at life’s cosmic footprint.

The road to acknowledging our cosmic ancestry may still be long, but it is inevitable. The universe, it seems, has always known what we are only beginning to accept: life is not confined to Earth.

Cover Image: A False-Colour image of a feature on Titan dubbed Xanadu. The origins of the feature are hotly debated. Titan may host two forms of life, with exotic biochemistry on the surface hydrocarbon lakes, and more familiar, carbon-based life forms in a suspected subsurface ocean. NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

Sources:

Extraterrestrial Life and Censorship

Interstellar Grains: 50 Years On

The Imperatives of Cosmic Biology

Further Reading:

If you like the idea or want to explore it more, here are a whole bunch of related articles.

Phew.

Leave a comment