The ingredients for the business of life have been found in meteorites, there is no question about that. A small group of scientists claim to have discovered something far more dramatic, microfossils. The discovery, if true has deep implications for our understanding of biology, evolution, and our place in the universe. Among the many theories that attempt to explain the origins of life, cometary panspermia is as elegant as it is provocative. This hypothesis suggests that life’s building blocks, or even fully-formed microorganisms, could travel through space aboard comets and meteorites, seeding planets like Earth.

Recent research published in Nature Astronomy, based on samples retrieved from the Asteroid Bennu indicates the presence of carbon, phosphate and organic molecules, as well amino acids and all five nucleobases. The material has a history of saltwater, providing a broth for the combination of these biomolecules. Bennu may just be a fragment of an ancient water world, destroyed in the chaos during the infancy of the solar system. This bit is the credible science, but now we move on to the incredible.

Panspermia challenges the notion that life is a rare event that emerged on Earth, and suggests an alternative, one where life emerged early in the cosmos, and sprouted wherever conditions were suitable. For this idea to gain traction, scientists must first find concrete evidence of extraterrestrial life—an endeavour that has turned to the study of meteorites, specifically carbonaceous chondrites.

Carbonaceous chondrites are among the oldest and most primitive meteorites in existence, remnants of the early solar system that contain organic compounds and water-bearing minerals. Some researchers have suggested that these ancient space rocks may also carry the fossilized remains of extraterrestrial microorganisms. If true, this would be a revolutionary discovery, confirming that life is not unique to Earth. However, the search for microfossils in meteorites has been fraught with controversy, with early claims dismissed as contamination or misinterpretation.

Early Claims and Initial Skepticism

The first reports of microfossils in carbonaceous meteorites date back to the 1960s, when George Clause and Bartholomew Nagy announced that they had found microscopic, life-like structures in samples of the Orgueil meteorite. They also detected organic chemical signatures consistent with biological activity. Excitement ran high—had they found extraterrestrial life?

Skeptics quickly raised concerns. Some of the supposed microfossils turned out to be terrestrial contaminants, including ragweed pollen. Others argued that the structures were the result of abiotic mineral processes rather than biological origins. This wave of criticism led to widespread skepticism, and the scientific community largely abandoned the idea that meteorites could contain fossilized life.

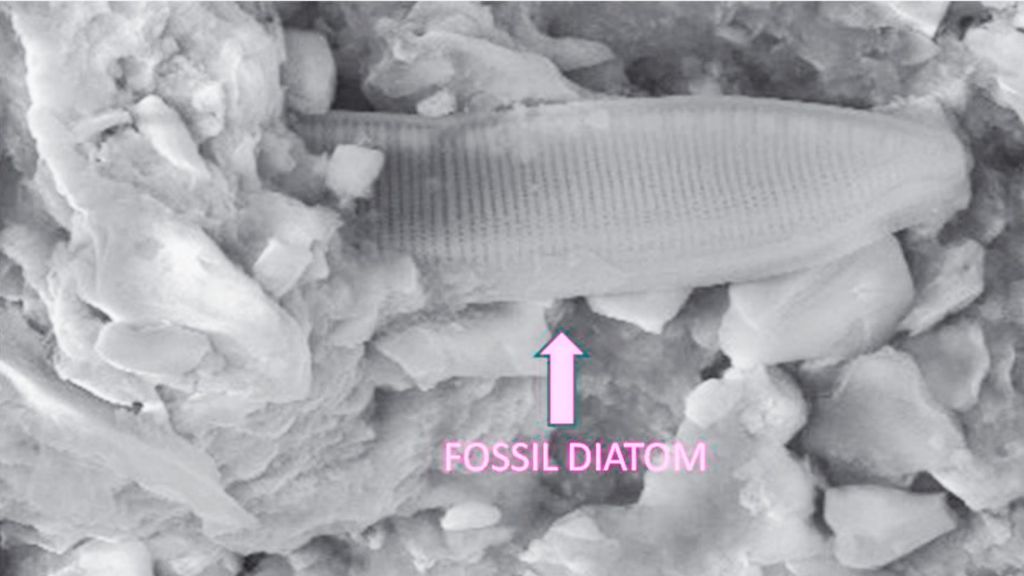

A cylindrical exoskeleton from the Polonnaruwa fireball.

Decades later, interest in the possibility of extraterrestrial fossils in meteorites was revived. Hans Dieter Pflug analyzed the Murchison meteorite using a method that dissolved its mineral content, revealing “organized elements” that closely resembled biological forms. His findings, though still debated, suggested that the dismissal of earlier claims might have been premature.

More recently, Richard Hoover used advanced electron microscopy techniques, including environmental and field emission scanning electron microscopy (ESEM and FESEM), to investigate meteorites. He found filamentous structures embedded in their matrices that closely resembled known terrestrial microbes. Chemical analyses showed that these filaments were compositionally distinct from the surrounding meteorite material, weakening the case for contamination.

Further supporting the hypothesis, researchers discovered siliceous diatom skeletons—tiny, algae-like structures—inside meteorites and in stratospheric dust samples. These findings, if confirmed, lend weight to the idea that life may travel through space aboard comets and meteorites, a cornerstone of the cometary panspermia hypothesis.

Cometary Panspermia

Critics argue that non-biological processes could create similar structures. However, certain microstructures, such as the intricate frustules of diatoms—composed of hydrated silicon dioxide—are highly complex and unlikely to arise abiotically. Moreover, elemental analysis of purported microfossils often reveals an internal composition matching the meteorite matrix, ruling out terrestrial contamination.

If microfossils in meteorites are indeed biological in origin, their presence strengthens the case for cometary panspermia. Carbonaceous chondrites are believed to be fragments of extinct comets, making them ideal carriers of microbial life. Comets, rich in water ice and organic compounds, could provide temporary refuges for microbes, enabling their survival across interstellar distances. Some scientists even speculate that liquid water pockets within comets, heated by radioactive decay, could serve as incubators for primitive life forms.

Stratospheric Findings

Supporting evidence for cometary panspermia comes not only from meteorites but also from Earth’s upper atmosphere. Clumps of viable but non-culturable bacteria have been detected in stratospheric dust collected from altitudes exceeding 40 km—far too high for Earth-based organisms to have been lifted by natural processes. Their large size and unique composition suggest an extraterrestrial origin, possibly from cometary debris.

Another intriguing phenomenon possibly linked to cometary panspermia is the red rain that fell in Kerala, India, in 2001. The red-colored cells found in the rainwater bore striking resemblance to structures seen in meteorites. While their origins remain uncertain, some researchers have proposed that they arrived on Earth following a meteorite explosion in the upper atmosphere, adding another layer to the panspermia debate.

A Cosmic Web of Life

If life indeed spreads through space via cometary panspermia, the implications for evolution are profound. Horizontal gene transfer—where genetic material is exchanged between unrelated organisms—could occur on an interstellar scale, shaping the development of life across the cosmos. Rather than life evolving in isolated pockets, planets and moons could be interconnected through a vast, cosmic exchange of genetic material.

The search for extraterrestrial life is far from over, but the evidence for microfossils in meteorites continues to grow. If confirmed, these findings would not only validate cometary panspermia but also redefine our understanding of life’s origins and its potential ubiquity in the universe. Future missions aimed at collecting and analysing cometary material could provide definitive proof of cosmic life. Until then, the possibility remains tantalizing: perhaps Earth itself was seeded by interstellar travellers, and the story of life is far grander than we ever imagined.

Cover Image: An alleged fossil diatom in a meteorite fragment recovered from Sri Lanka.

Additional Sources:

Primordial planets, comets and moons foster life in the cosmos

Bacterial morphologies in carbonaceous meteorites and comet dust

The Imperatives of Cosmic Biology

The Polonnaruwa meteorite: oxygen isotope, crystalline and biological composition

Leave a comment