For centuries, humans have wondered about the origins of life. The predominant theory is that it spontaneously arose on a primordial Earth, from a soup of building blocks delivered by comets, in regions of fluctuating dryness, possibly aided by lightning strikes. There is however another theory, called panspermia going back to the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras who lived in the 5th century BCE, suggested that the seeds of life were distributed across the cosmos and were delivered to planets.

In 1834, Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius discovered organic molecules in a meteorite, introducing the idea that organic molecules from space could provide the building blocks necessary for life to spring on terrestrial worlds, a view that is now widely accepted. Later in the 19th century, the British Mathematician William Thomson proposed that life on Earth had an extraterrestrial origin, transported by asteroids and comets. In 1903, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius suggested that pressure from stellar winds could distribute spores of life between worlds.

By the 20th century, there was a space transport architecture for life, including escape from a planet, a transit between planets, and landing on recipient worlds. Extrapolating this idea allows for imagining biospheres spread across entire clusters of galaxies.

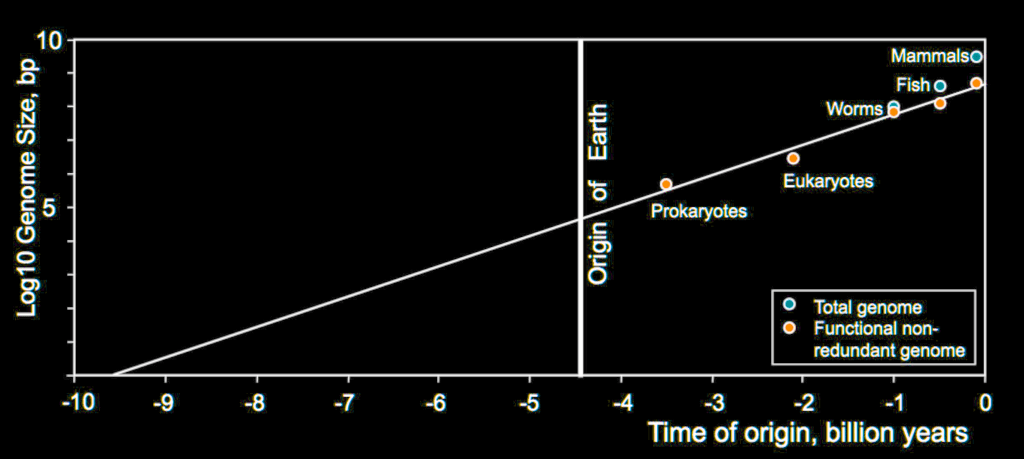

A plot of the increase in complexity of life, that follows a straight line. A straight line that goes back to well before the formation of the Sun, back to the dawn of the universe. From a paper by Alexei A. Sharov and Richard Gordon. A version stopping at the formation of the Earth was published in an earlier paper by Sharov.

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for panspermia is the discovery of complex organic molecules in deep space. Interstellar dust clouds, comets, and meteorites are filled with biochemically significant compounds. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which form the backbone of many organic molecules, have been detected in vast quantities throughout the Milky Way and beyond. The Murchison meteorite, which fell to Earth in 1969, contains an astonishing diversity of organic compounds—some of which predate our planet itself. These findings suggest that the ingredients for life are not unique to Earth but are instead a common feature of the cosmos.

Interstellar Life

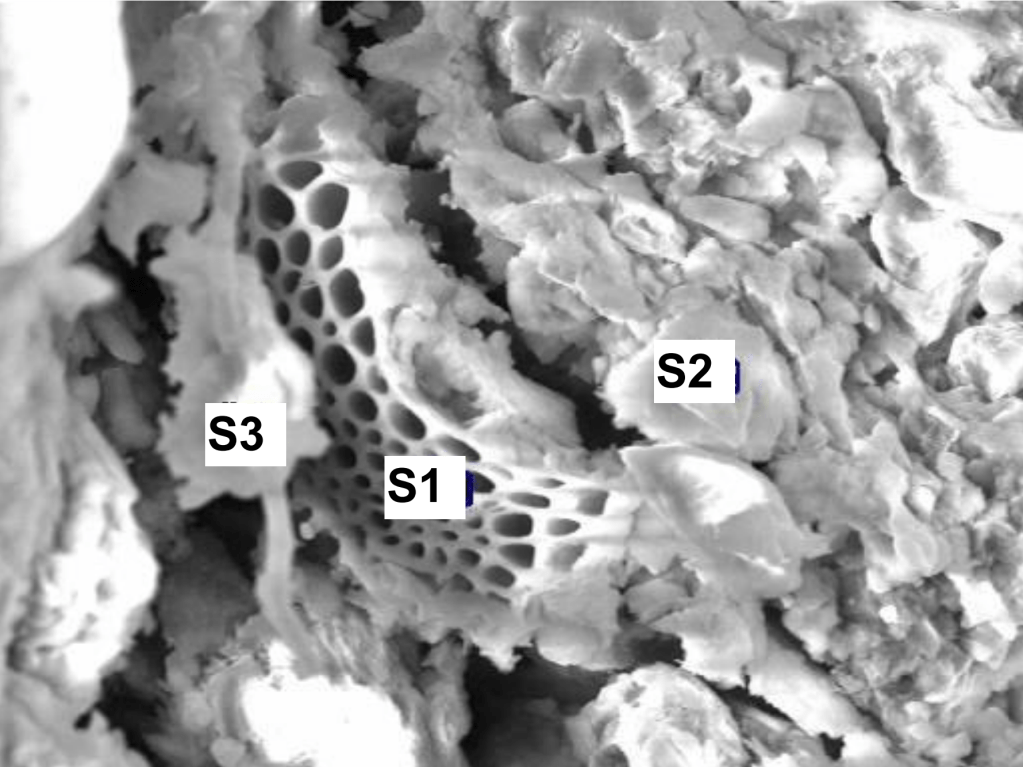

More tantalizing still is the presence of microscopic structures resembling fossils in certain meteorites. Carbonaceous chondrites, meteorites thought to originate from comets, contain formations that bear striking similarities to cyanobacteria. Some researchers argue that these structures are the remnants of ancient extraterrestrial microbes. Even more controversially, diatoms—complex, silica-based microorganisms—have been reportedly found embedded within meteorites, suggesting a biological lineage far older than our planet.

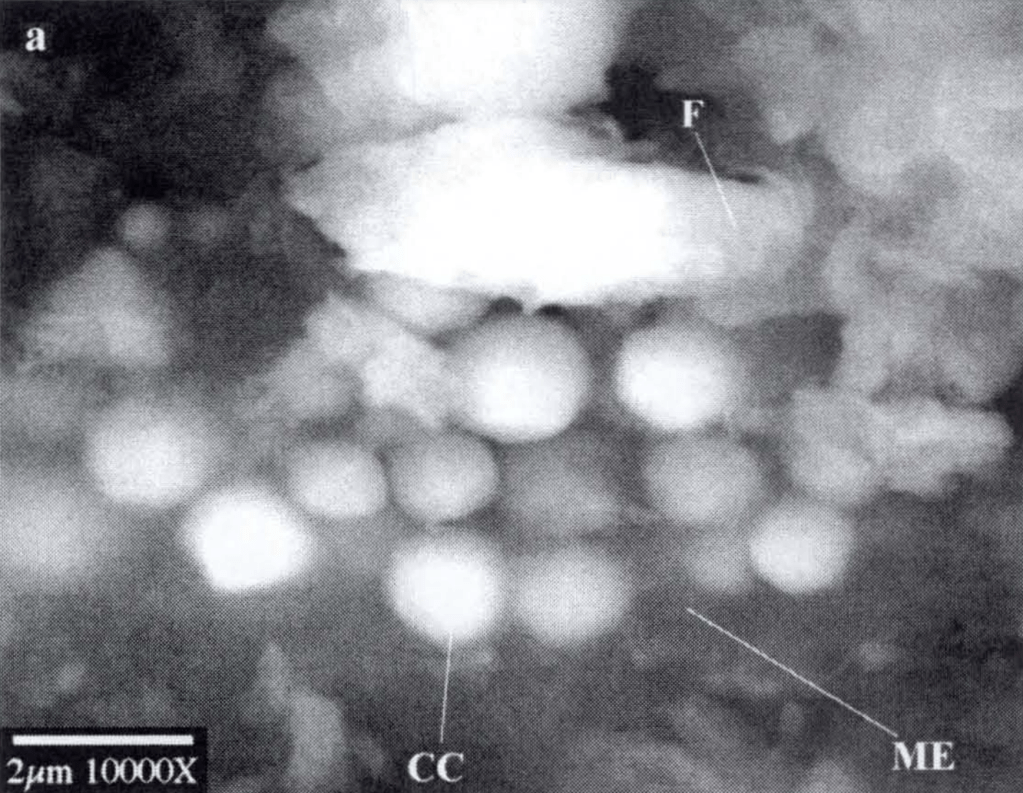

A colony of what appears to be spherical cells held together by a mucous slime, within the Murchison meteorite. (Image Credit: Richard B. Hoover/NASA).

A technologically advanced species that springs up on a terrestrial world around a gently burning star may struggle to hop between planets, while the universe may have a built-in transport system to allow life to hop between stars, and scientists have proposed a number of mechanisms for such interstellar migration. Cometary panspermia proposes that comets serve as microbial incubators, protecting and propagating life within their icy interiors before releasing it into space. When comets pass near young planetary systems, microbial life could be scattered onto new worlds, propelled by radiation pressure from their host stars.

A second mechanism involves planetary ejection. When large impacts strike planets, surface material—including any microbial life—can be blasted into space. Some of these fragments may travel for millennia before landing on another habitable world. Earth itself has likely sent microbial-laden rocks into space following asteroid impacts, meaning that if life exists elsewhere in the solar system, it may have originated here.

Another possibility is cosmic gene exchange through horizontal gene transfer. On Earth, bacteria and viruses regularly swap genetic material, enhancing their adaptability. Some scientists propose that this process could occur on a cosmic scale, allowing genetic information to spread between planets and even across star systems.

Red Rain

Despite these intriguing possibilities, panspermia faces significant challenges. The vast emptiness of interstellar space is hostile to life, with extreme radiation, frigid temperatures, and high-velocity impacts posing significant threats to microbial survival. Yet, life on Earth has proven astonishingly resilient. Certain bacteria and archaea thrive in environments once thought too extreme—inside nuclear reactors, beneath Antarctic ice, and even in the vacuum of space. Microbes trapped in amber have been revived after millions of years, and ancient ice cores have yielded bacteria still capable of reproduction. Such discoveries lend credibility to the idea that life could endure an interstellar journey.

Suspected degraded biological material from a meteorite fragment recovered in Sri Lanka after a fireball in 2012. The paper is controversial. Jamie Wallis, Nori Miyake, Richard B. Hoover, Andrew Oldroyd, Daryl H. Wallis, Anil Samaranayake, K. Wickramarathne, M.K. Wallis, Carl H. Gibson, N. C. Wickramasinghe.

One of the most unusual pieces of evidence for an extraterrestrial origin of life comes from an event in Kerala, India, in 2001. For weeks, the region experienced a bizarre phenomenon: red-coloured rain. Scientists analysing the particles responsible for the coloration found cells unlike any known terrestrial microorganism. These “Red Rain” cells lacked DNA but showed remarkable resistance to extreme temperatures, leading some researchers to speculate that they might have originated from space, possibly delivered by a meteorite.

A Cosmic Heritage

Beyond the mechanics of life’s transfer, some cosmologists propose that life is not just a passive passenger but an active force in the universe’s evolution. Hydrogravitational dynamics (HGD) cosmology suggests that the early universe formed countless primordial gas planets, which could have acted as cradles for the first life. If this is true, life may have begun almost immediately after the Big Bang, spreading across the universe through cometary panspermia and dark matter planet-clumps. Some even argue for a “Biological Big Bang,” in which life was seeded in multiple locations simultaneously, accelerating the emergence of complex ecosystems on young planets.

If panspermia is correct, it would fundamentally alter our understanding of life’s place in the universe. Rather than being a rare accident confined to Earth, life might be an intrinsic part of cosmic evolution, threading through the fabric of galaxies. It could mean that somewhere, on a distant exoplanet, organisms related to us—sharing the same molecular ancestry—are evolving in ways we can scarcely imagine.

Illustration of the Europa Clipper mission. (Image Credit: NASA).

As new missions probe the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, search for biosignatures on exoplanets, and analyse the chemistry of interstellar objects, the question of life’s origin remains open. Whether we find direct evidence of extraterrestrial biology or not, the theory of panspermia forces us to reconsider the cosmic potential of life—and, perhaps, our own extraterrestrial heritage.

The question here is really what do you choose to believe, that life is a rare accident that only occurs in conducive environments, or that our whole universe is habitable, not just our planet.

Cover Image: Illustration of the Fountains of Enceladus by NASA SVS.

Sources:

The Imperatives of Cosmic Biology

Primordial Planets Explain Interstellar Dust, the Formation of Life: and Falsify Dark Energy

Bacterial morphologies in carbonaceous meteorites and comet dust

Primordial planets, comets and moons foster life in the cosmos

Leave a comment