Beneath our feet, the Earth occasionally rumbles and shifts, releasing built-up stress in the form of earthquakes. The ground trembles, buildings sway, and waves ripple through solid rock and liquid magma alike. But what if this same phenomenon could be found on a scale so vast that it shakes the very fabric of space itself? Deep in the cosmos, the remnants of once-mighty stars—neutron stars—experience their own seismic events: starquakes. Like their terrestrial counterparts, these stellar convulsions arise from the sudden release of accumulated stress, though the forces involved are nearly incomprehensible.

Stress Accumulation: A Cosmic Pressure Cooker

On Earth, the slow movements of tectonic plates generate stress along fault lines, storing energy until the crust gives way in a quake. On neutron stars, stress accumulates through entirely different but equally formidable mechanisms. These ultradense remnants of exploded stars are cosmic dynamos, spinning rapidly while hosting some of the most intense magnetic fields known to science. As time passes, these magnetic fields decay and twist into unstable configurations, exerting tremendous pressure on the rigid crust of the star. At the same time, the star’s rotation slows due to magnetic braking, causing a shift in centrifugal force. This slight change in equilibrium further stresses the crust, much like how a cooling, contracting planet experiences surface fractures over time.

Much of this stress accumulates at the equator, where the crust is farthest from the magnetic poles. If a neutron star is born spinning rapidly, it may develop an equatorial bulge, increasing the likelihood of fractures as its rotation decelerates. These cosmic stress factors build up over thousands or even millions of years, waiting for the inevitable breaking point.

Crustal Rupture: A Stellar Fracture Event

Just as an earthquake occurs when the strain along a fault reaches a critical threshold, a neutron star’s crust can only endure so much tension before it cracks in a sudden, violent event—a starquake. The rupture unleashes immense energy, estimated at around 10⁻⁹ of the neutron star’s gravitational binding energy, equivalent to a cataclysmic explosion many times greater than all nuclear weapons ever detonated on Earth. In extreme cases, these quakes trigger giant flares, sending shockwaves through the star and leaving it ringing like a cosmic bell.

The theoretical framework governing these quakes predicts that they alter the neutron star’s moment of inertia, slightly changing its spin rate. These glitches—sudden increases in a pulsar’s rotation—offer one of the most direct observational signatures of starquakes. The fractured crust momentarily redistributes mass, leading to a measurable shift in angular momentum. The location, magnitude, and frequency of these glitches provide astrophysicists with clues about the internal structure of neutron stars.

Observable Consequences: Flares, Glitches, and Fast Radio Bursts

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound? The same question might be asked of starquakes—how do we know they happen? Unlike earthquakes, which we detect with seismometers, starquakes announce themselves through bursts of high-energy radiation. When the magnetic field lines of a neutron star suddenly reconfigure following a quake, they generate intense currents that produce gamma-ray flares. These flares are often observed from highly magnetized neutron stars known as magnetars, whose violent starquakes generate some of the brightest explosions in the universe.

Starquakes also leave their mark on a neutron star’s rotation. In pulsars like the Crab and Vela, glitches provide strong evidence that intense crustal fractures lead to spin changes. In some cases, the cracking of the crust could trigger particle outflows or magnetic reconnection events, affecting the star’s long-term evolution.

Intriguingly, the first repeating fast radio burst (FRB) ever detected displayed a frequency-magnitude relationship similar to earthquakes. This suggests that some FRBs could be the cosmic echoes of neutron stars fracturing under extreme pressure, with escaping plasma generating the brief, mysterious radio signals that puzzle astronomers.

Beyond the Fracture Model: Alternative Theories and Open Questions

Despite the compelling similarities between earthquakes and starquakes, some astrophysicists propose alternative explanations for the violent disruptions observed in neutron stars. One theory suggests that rather than simply cracking, the crust may undergo episodic eruptions of highly compressed gas rich in electron-positron pairs. These eruptions could momentarily expel matter into space before the crust reseals itself, releasing energy comparable to that of giant pulses (GPs) and FRBs. If the size and duration of these fissures are large enough, they might account for some of the extreme high-energy events seen from magnetars.

Another layer of complexity comes from the interplay between a neutron star’s crust and core. The core’s oscillations, coupled with the magnetic field, may explain the multiple quasi-periodic oscillations (QPOs) observed in giant magnetar flares, such as the historic event from SGR 1806–20. These oscillations hint at a deeper, more intricate mechanism behind the tremors of neutron stars—one that scientists are only beginning to unravel.

The Universe Quakes On

In the grand dance of celestial mechanics, where galaxies collide and black holes consume stars, the tremors of neutron stars might seem like mere ripples in an ocean of chaos. Yet, they offer profound insights into the nature of matter under extreme conditions, the life cycles of the most extreme objects in the universe, and the mechanisms that drive some of the most powerful explosions known to science.

The next time the ground shakes beneath your feet, consider that somewhere, out in the cosmos, a star may be quaking too—its crust cracking, its spin shifting, and its energy radiating across the universe in a cosmic symphony of destruction and renewal.

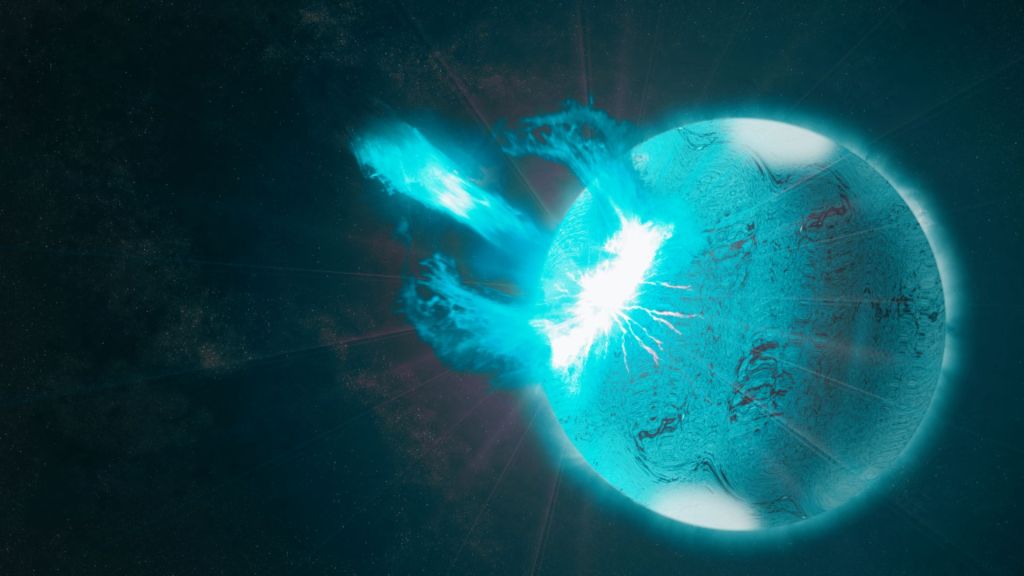

Illustration of a Starquake on a Neutron Star. (Image Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/S. Wiessinger; Fermi).

Leave a comment